The Heart, Soul, Mind, and Body of a Poem: A Conversation with Dorothy Nielsen

A Conversation between Dorothy Nielsen & Meg Freer

Dorothy Nielsen’s lifelong engagement with the arts began early when she was a cellist and cello teacher before earning a PhD in literature and becoming a professor. She has authored essays and taught courses on topics from nature poetry through Christian writers and Canadian fiction. Her poems appear in many journals including The Literary Review of Canada and Christianity and Literature, and in her poetry collection. New works by Nielsen are forthcoming in The Alchemy of Stories: Essays on Literature and Life and in Paradoxa by Solid Food Press. She serves on the Advisory Board for Traces Journal.

Dorothy Nielsen was interviewed by Meg Freer via a Zoom conversation in the autumn of 2025.

Meg Freer, for Traces: Dorothy, you have a literary background, having been an English professor for many years, with an interest in the religious and metaphysical poetry of George Herbert and Gerard Manley Hopkins, and you’ve written both literary criticism and poetry, including a book of poetry, The Persephone Papers. How did you decide to become a professor? And tell me how some of your first publications came about.

Dorothy Nielsen: I loved literature so much from an early age, and I think that’s what drew me to study it in great depth. Out of that love came writing poetry as well. My first poem was published, to my surprise, when I was nine years old. I remember it forming one night in my head, and the next morning I printed it out. I must have shown it to my teacher because at the end of the year, I was handed a book produced by the board of education that had about 100 poems from kids across the city.

During my university years, I sent some of those many poems I was always writing to student publications, and eventually, I sent a couple, when I was in grad school, to The Fiddlehead. That was my first professional publication.

Traces: And as a professor, you would have written academic articles.

DN: Yes, that was one requisite for getting and keeping my job, and those flowed very naturally out of my PhD dissertation and my teaching interests over the years.

Traces: Did you ever find it difficult to switch between academic and creative writing?

DN: To some degree. That was why when I was a full-time academic, one corner of my study had bookshelves and a computer station for lecture prep, research, and marking, and in another corner, I set up a desk beside my poetry shelf. So I divided myself between two halves of the room.

Traces: Like me, you grew up in the United States and now make your home in Canada. How long have you been in Canada, and where do you consider to be home?

DN: For most of my life, I’ve crisscrossed the border, actually as well as spiritually. When I was eight, my family moved from South Bend, Indiana, to Windsor, Ontario, where I loved living. Being in a border city, I crossed back and forth a lot, often once a week when I played cello in the International Youth Symphony as a teenager. My family went back to live twice in the U.S. when I was ages 9 to 10 and then 17 to 18, and there were a lot of visits because I have so many relatives and in-laws there. Besides having strong family ties in both countries, geographically, I still feel partially rooted in the three states I lived in, which included Connecticut and Minnesota.

Then something happened to me. When I was 27 years old—a Permanent Resident of Canada but a U.S. citizen—my husband and I drove across Canada from Ontario to Victoria, British Columbia. I fell so deeply in love with the lands and skies along the Trans-Canada Highway that I knew by the time I got back, I would become a Canadian citizen, which I did shortly after. So both are home, but in different ways.

Traces: Your poems and essays have appeared in Traces Journal, and you’re now on this journal’s Advisory Board. What are some reasons you enjoy supporting and writing for a journal with a specifically Canadian focus?

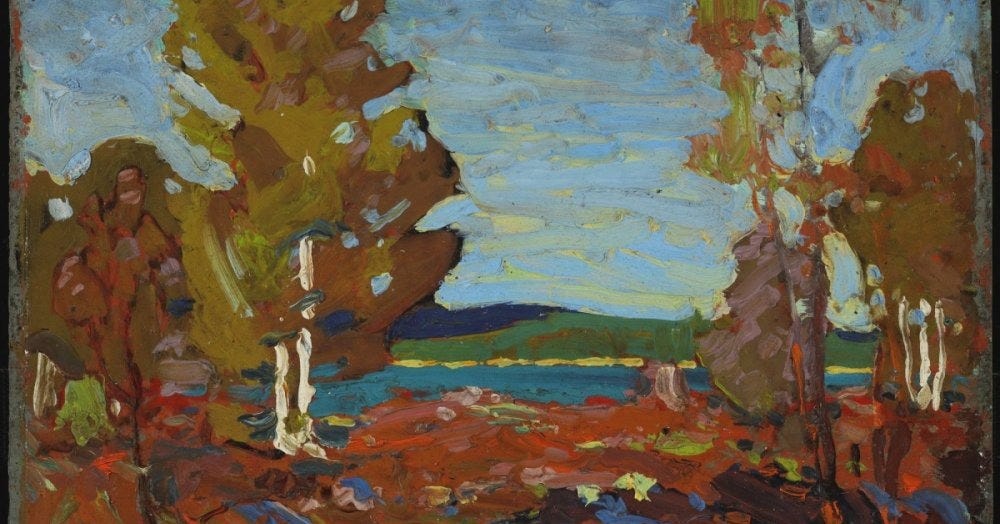

DN: I’ve had a visceral and imaginative love of Canadian painting since I was a teenager and lived a block away from an old mansion called Willistead Manor, where the Windsor Art Gallery was housed. I spent hours there, and the gallery’s Canadian landscape paintings really struck a chord in me. These paintings now recall to me, to borrow a term from the Traces mission statement, our ‘shared geography’ along the Trans-Canada Highway that I fell in love with. So I appreciate Traces Journal’s emphasis on both Canadian writing and Canadian visual art.

What’s more, unlike in the U.S., there are very few literary journals in Canada that welcome both free verse and fixed form poems that engage with the Christian tradition. So I think Traces, with this multifaceted ethos, is a vital addition to what we’ve had so little of until recently in Canada.

Traces: As you point out, the difference with Traces Journal is that it incorporates Christian thematic material as well as visual art. It’s interesting that you came to the journal, in a way, through visual art. What role can Traces play in the future of the contemporary Christian arts scene?

DN: I’ve been thinking a lot about the way that Traces integrates heart, mind, body, and soul. I recently finished listening to a series of lectures on contemplative prayer, where the teacher was emphasizing how the Christian faith necessarily involves all four sides of a person working together. I think this is one of the values Traces exemplifies. Of course, we find the heart everywhere in Traces, in the poetry and the visual art, and we have the intellectual tradition in the poems and essays and interviews. And the journal pays close attention to the physical expression of truth, goodness, and beauty by showcasing our rich heritage of visual arts and by publishing beautiful free verse and formalist poetry that draws attention to the musicality of language. Traces feeds our soul with its Christian themes, and on top of all that, it offers the integration of heart and head with Norm Klassen’s column “The Order of Love.” I believe the journal provides an exceptional model of how to weave together these four features of faith.

Traces: Readers of Traces will probably agree with you wholeheartedly. I have a question about integrating one’s faith into the act of writing, particularly intellectual writing. You returned to the Catholic faith a few years ago after a deliberate break with it, and you wrote a philosophical essay about this for Traces—“The Fire that Breaks from Thee.” In that essay, you discuss how your reconversion affected your reading and writing of specifically religious poetry. Tell me a bit more, in everyday language, how creative writing can be an act of faith first, as opposed to an intellectual exercise informed later by faith.

DN: I think I can answer this by telling the story of the integrated arrival of the poem “The Other Dream of Scipio.” One day this summer, I was out walking in nature while I was praying the rosary with soul, mind, and body, along with a heartfelt plea to God for an end to two of our biggest wars. I had just finished my passage of spiritual reading, of C.S. Lewis’s description of Cicero’s “The Dream of Scipio” in The Discarded Image. Suddenly, I was seized by an image of the hero in the upper spheres and by the agonized thought, “I wonder what Scipio, looking down at our war-torn earth, would think of us.” Poetic inspiration zapped my body and soul, and I recognized the signs I experience whenever a poem begins to stir: a sudden thought that I sense is a poetic line, combined with a unique feeling tone, plus a clear image and a burning need to capture all this on paper. I returned to prayer, and when I was done, I immediately started to write. Almost all of the finished work came out very quickly without any planning. As I wrote, I felt a growing sense of gratitude and awe for Christ’s sacrifice on the cross, and awe at the courage of dying soldiers, and for anyone who exemplifies Christ’s saying that there is no greater love than to lay down one’s life for one’s friends, reflected in crucifixion and sacrifice imagery throughout the piece.

So this poem was born directly as a result of the faith which had allowed me to make that emotionally-charged plea to God and had led me to read a Christian author, in a multifaceted process of religious writing via soul, heart, intellect, and body.

Traces: I personally think that an important aspect of this experience you had is that you were outside walking. Moving our bodies allows for connections we wouldn’t be able to make if we weren’t active. My next question directly follows from that story of your poem’s arrival.

Whether you’re writing lyrical free verse or more formalist poetry, you have an enviable ability to draw together seemingly disparate concepts into a seamless continuity. Heart and mind, soul and intellect, and faith all come together very naturally. For example, in your poem “Dark Matter” in the previous issue of Traces, I liked that you used the pantoum form. The repeated lines really elegantly efface the contrasting images of dark and light, and a child who’s present and not present.

And similarly, in the poem “For Your Death Day,” which appeared in Literary Review of Canada, you write of foundations coming together and apart, earthly and cosmic occurrences, past time and present time. That’s like the Scipio poem, where you had this vision of Scipio up in the heavens looking down on our earth—someone from the past looking at the present. A former student of yours has said about you: “The connections she weaves are not merely literary but experiential, adding up to something larger, something close to transcendence.” It seems this transcendent experience probably couldn’t happen without some basis in faith.

Your Scipio poem wasn’t really planned in advance, in terms of how it was going to look or what literary techniques you were going to use. It was very instinctive, maybe planned in your head as you walked, but is that the way many of your poems happen now? In your current poetry writing practice, how much do you plan out in advance in terms of rhythm, form, and literary techniques? Or is your writing more instinctive, following sparks of inspiration?

DN: What happens to me is always the same, no matter what comes out in the long run, whether in fixed form or as free verse. Spontaneously, one or two lines drop into my head along with a unified intuition that includes an image, a feeling tone, and a multifaceted, complete thought which seems like a skein of wool with a leading thread that I intensely want to unwind in words as I follow it to the end.

The initial writing process is likewise intuitive because I choose my form based on the rhythm of those initial lines, and the first drafts just fall unplanned onto my notebook pages. Sometimes, in the second or third draft, I realize the piece has shaped itself into a different genre and that I’m writing in another fixed form or free verse.

So the first few handwritten drafts are primarily inspiration, or the first 10 or 15, because I write out about 20 to 40 drafts of any one poem, a new draft each time I make even a minor adjustment. In the later drafts, there’s more strategizing, which might include, say, the substitution of more harmonized metaphors, but it is concerned with how to stay true to that original integrated ‘zap’ that came into my soul, mind, heart and gut. The editing takes more time, but the initial multifaceted intuition makes up most of the final text.

Even if I am thinking of writing formalist poetry, for example, for the fixed form groups I meet with, I always trust instinct, and the groups stipulate that we should remain open, no matter what genre we are aiming for, to writing in any style—fixed form, free verse, or prose—that might take us by surprise. Once, a member even ended up making a collage.

Traces: That feels like a familiar process to me, and even the skein of wool image is evocative for me, because a skein of wool is itself a fixed form. The way you pull the wool out is not a straight line, and it doesn’t always unravel the way you think it’s going to unravel. I think that applies to many art forms. You can start with a design you have sketched out, but once you get going with the rhythm of whatever it is you’re doing, sending the shuttle back and forth, or spinning, your instinct might take it in a different direction in the end.

You are a musician. What relative importance do musical elements play in your poems: rhythm, structure, narrative, the imaginative element? Do you find a musical connection, or does the connection happen instinctively because you’re a musician first?

DN: When I was twelve, I started playing cello and also devouring the musical sonnets and other formalist poems of Edna St. Vincent Millay. The immersion in both arts has attuned me to the role of the body involved in making all styles of poetry by teaching me not only to highly value the sounds, rhythms, and tones of a literary composition but also to recognize the physical ‘zap’ that happens when a poem is making itself known.

And both arts primed me to seek in my reading and writing the wild depths and heights of imagination and emotion that a lot of my favourite writers—and composers—take me to, even when they begin with everyday images. For example, Denise Levertov, the poet I’ve written most of my literary essays about, uses what’s known as the ‘Deep Image’ when she meticulously describes “the here and now” in such a way that everyday details become a portal to psychological, spiritual, and divine planes.

Traces: There’s a lot of discipline required in learning to play any instrument at a high level. Classical music training, at least the way I was taught, was very structured in terms of learning music theory and learning to read someone else’s notes on the page. I wasn’t taught to improvise. The way you describe your writing process is not rigid like that at all, but there still must be that discipline that we have learned as classical musicians. How do you relate the musical training to your poetry in terms of discipline? Do you think it has either restricted or released possibilities for poetry?

DN: I think this kind of disciplined training in musical forms and theory has always helped me write poetry in traditional genres. Fixed poetic forms inhabit my head partly because I immersed myself in them by reading formalist poems at the same time I studied cello and music theory, even while I was also studying the grammatical patterns of English and other languages. Every time we train ourselves to recognize the beauty of any artistic structure or linguistic form—along with the paradoxical freedom found through all these structures to fully access a poetic intuition—we strengthen our ability to recognize beauty in traditional genres or free verse and to create it freely in our own writing.

Traces: You get that ‘zap,’ as you say, which is already a reward before you start writing. Or if you’re working on a piece of music and suddenly you play a phrase just the way you’ve wanted to, that’s a reward in itself. Is the process of learning a piece or writing a poem the reward, or is it when you think your poem or piece of music is ready to share with other people?

DN: My writing process has always included the desire for a completed, ready-to-share artifact because the initial intuitive inspiration entails an intense need to make it into the form of a work on a page, a product that looks like the mysterious poems I loved the look of in books as a preschooler, even before I knew how to read.

However, once a poem is polished and ready to be read, I might keep it private for years or forever. I have written hundreds of finalized poems, but I only desire to publish a small percentage. I complete many as what’s been called ‘soul writing’—just experiencing the process for the sake of my soul.

Traces: Back to the poem “The Other Dream of Scipio,” it’s a meditation on what the ancient Greek general would think if he were looking down from the heavens on our present chaotic world. And it’s such a bleak view. But your poem has a lyric flow to a hopeful ending, that maybe Scipio would hear the heavenly music that promises we’re not aimlessly wandering in the cosmos until our death, and that we have a place ‘among the stars,’ as you put it. I find a lot of hope and joy in this poem despite its premise. I’m wondering, now that you have said this poem came mostly by instinct as a result of reading C.S. Lewis, do hope and joy often play a part in your creative process? Is that something you’re interested in expressing?

DN: When these feelings flow from the original multifaceted intuition, yes. About a third of my published poetry reflects pure joy, another third is woeful and worrying, and the rest is a mix of light and dark, along with neutral-toned works. In the Spring 2025 issue of Calla Press Journal, Living in Wonder, the editors laid out three of my poems in a two-page spread, and at a glance you can see pieces that range from a joyful celebration of marriage with just a hint of life’s complexities, through a simple statement of delight in the memory of watching a boy running with a dog, to a mournful midlife meditation on time passing. Since my own poetry arises from my intuitive “feeling/thinking” experiences, it will necessarily reflect all the shades of light and dark I encounter in the world and inside myself.

Traces: I think you have to feel you have balance in your life to be able to write a balanced output like that.

DN: And you have to want to share it. There are some sides certain poets just don’t want to show in public, of course. Though it might sometimes be risky to bury them. Denise Levertov wrote an essay when the poet Anne Sexton committed suicide, in which she blamed Sexton’s audience, editors, and publishers for egging her on by valuing only her darkest confessional works. Levertov warned young poets: Don’t just dwell on one side of yourself. If you can, explore the positive in life. Don’t become a tragic poet just because that’s what’s selling right now. Naturally, though, some people do live a life that is either predominantly sorrowful or joyful, and certain wonderful poets I read choose for whatever reason to show only one side of life.

Traces: How have you balanced these varied but complementary interests of music, teaching, writing literary criticism and poetry, while also navigating family and career responsibilities?

DN: I’ve always opted to put onto the back burner any interests that aren’t my main duty at the time. When I started grad school, I quit the musicians’ union and stopped accepting playing gigs. Years later, when I became a mother, I resigned my full-time academic position so that I could focus on that role for a couple of decades, and when I went back, I taught only part-time. These are the reasons that I didn’t set out to publish much poetry until I was well into my 50s.

Traces: What projects are you working on now, or do you let ideas happen without having bigger names for them, like ‘project’?

DN: I’ve been putting together a collection of poems. My forms and themes have evolved a lot since my collection The Persephone Papers appeared twelve years ago, so I’ve been gathering recent poems to present a different side of my work.

Traces: You have a teaching legacy, and now you’d like to leave a poetic legacy in the form of a new collection. Are there any other creative legacies?

DN: I didn’t realize how much it would mean to me that one of my legacies would be the pleasure of watching students take up creative, literary work.

Traces: That’s both a personal legacy and an academic legacy.

DN: That’s true! I find that one of the many gifts of getting old is having a long perspective that lets me recognize previously unseen meanings of past actions and events. Nowadays, one of my favourite passages from T.S. Eliot comes at the point in “Little Gidding” that describes a former intention being “only a shell, a husk of meaning/ From which the purpose breaks only when it is fulfilled.”

Meg Freer grew up in Montana and now lives in Kingston, Ontario. She holds two music degrees and a creative writing certificate and is a member of The Ontario Poetry Society and League of Canadian Poets. She is also Poetry Co-editor for The Sunlight Press, a Contributing Editor for Traces Journal, and co-host of a monthly series featuring poetry performed simultaneously with live improvised music. Her prose, photos, and poems have been published in many journals and in four chapbooks. During 2024-25, she served as Poet-in-Residence for the McDonald Astroparticle Physics Institute at Queen’s University.