To look lovingly is not to miss the real truth about something, but to find it.

Why does this magnificent book title work so well?

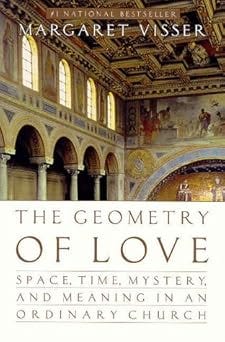

Canadian cultural anthropologist Margaret Visser’s subject is a church in Rome built over the tomb of Saint Agnes, a child martyr of the early fourth century. The book, subtitled Space, Time, Mystery, and Meaning in an Ordinary Church, guides its readers through this church, Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura.

The Geometry of Love explains the meaning of architectural details in a building designed to reveal God’s love and elicit a response to that love. The title suggests that divine love expresses itself with a beauty and complexity for which geometry serves as an apt metaphor; it acknowledges and encourages responsiveness to God in craftsmanship; it conveys the notion of a contemplative endeavour (both individual and collective) called into being by the reality of love; and it affirms a transcendent wholeness, the implications of this love constantly unfolding, repeatedly surprising those devoted to it.

For Visser, the way to understand a church is to enter it and inhabit its meaning both physically and metaphorically. She challenges a modern intellectual assumption, that “in order to understand something you are always better off not participating in it.” Detachment was once the gold standard of the scientific method, though twentieth-century developments helped to change that perception. Visser observes that it is now recognized that no one has “a blank slate of a mind, it is therefore detrimental to truth to claim total objectivity.” Truth and objectivity are not the same thing. Participation betokens something like heartfelt and vulnerable engagement. To look lovingly is not to miss the real truth about something, but to find it.

Visser makes two basic points about Christianity that I find resonant for my theme. The first is that The Geometry of Love acknowledges and affirms contradiction and paradox: “my mind embraced a vast contradiction”; “churches remain – but they remain in order to keep alive a message that is all about movement, about hope and change. In short, a Christian church seems to be – and quite consciously is – a contradiction in terms”; “church and world form a paradoxical pair, in which Christians are expected to be totally devoted to the world, yet not to be taken in by it”; “Christians do not believe that culture has the last word over morality …. Yet for Christians, culture is to be entered into …; there is no such thing as belief unmediated by culture.” The author happily affirms that Christianity insists on going beyond the limits of rationality, though many take this insistence as an affront.

The second is that the paradoxes of Christianity are evoked by the language of love and reason in tension, with emphasis on the revelation of love: “For a thousand years Christians had insisted on the divine half of the great paradox of Christ’s simultaneous divinity and humanity; from now on the mystery of God’s love, of his insistence upon entering into the human condition, would receive the greater share of Christian attention.” One might say that for a thousand years Christians had insisted on the veracity of Christ’s divinity, and subsequently what his self-emptying in the incarnation meant as an expression of love. For Visser, the tension between truth and love in Christian revelation has a historical dimension.

A church, as the embodied expression of a comprehensive vision of reality, provides its own cues for the aesthetic meaning and value of its features.

If the paradoxes of Christianity upset dated scientific expectations, they also challenge pernicious aesthetic ones. One of the chapels of Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura emphasizes devotion to the Sacred Heart. The architectural and pictorial representation of this devotion disturbs contemporary aesthetic assumptions about sentimentality, banality, and vulgarity. Visser wants the reader and the visitor to the church to recognize that representation must be appreciated in context. A church, as the embodied expression of a comprehensive vision of reality, provides its own cues for the aesthetic meaning and value of its features.

The relationship between reason and the heart in The Geometry of Love finds its sublime expression in loving responsiveness to God. Paradoxically, responding to God begins not in the self but in God, who is always already at work in the human heart. The self is not a self-contained rational, decision-making entity; at every turn, it encounters love. In looking forward, as well as backward, the soul confronts a personal reality. Visser borrows the revelation shown to Julian of Norwich: “‘I am what you mean.’” Meaning transcends facts and concepts; it is God himself, the supremely personal reality to whose love we are called to respond, both individually and communally.

The revelation in the Crucifixion and Resurrection is an epiphany of God’s love: “It was the ultimate epiphany of his love,” Visser writes. Freedom accompanies this love, beginning with the freedom to respond to it. God’s kingdom is revealed in a drama concentrated in the sacrifice on the altar, a kingdom of mercy and forgiveness glimpsed only as one participates in it: “Only the freedom inherent in giving, and ultimately the ability to love … somebody who has harmed you, defines forgiveness…. And no law can prescribe forgiveness – it has to come from the individual heart.”

Visser leans into the language of reason and love here: forgiveness finds definition in the act of giving; it eludes law to be found only in the heart.

The revelation of God’s love occurs and is celebrated on the altar. The order and design of the church are centred here, even though no human endeavour can express the depths of this sacrificial love. The passion of the Lord defies understanding, something the apostle Paul talks about when he says that for a good person one might perhaps be willing even to die, but Christ showed his love for us in that he died for us while we were still sinners.

For one will scarcely die for a righteous person—though perhaps for a good person one would dare even to die—but God shows his love for us in that while we were still sinners, Christ died for us.

Romans 5:7-8

The altar is also the place of the fulfillment of the soul’s desire. In Sant’Agnese fuori le Mura, the tomb of the child saint lies directly below it. The altar gives ultimate meaning to Agnes’s suffering. In imitation of Christ, martyrs like her bear witness in a way beyond the power of words to explain.

The opposite of the law of love is the system of shame and revenge, which appeals to the logic of balance, symmetry, and accounting. A culture embracing such a system, Visser observes, “usually believes also in fate.” Fate assumes a closed, logical system, anthropomorphized as the actions of the gods or reduced to the supposedly explainable interactions of material processes. Meaning, purpose, and freedom evaporate. Reason itself is lost in a self-devouring death spiral.

For Visser, when reason submits to love, it flourishes. Reason thrives in the context of love as “geometry” in the fullest possible sense of that mathematical word. A church is the fruit of love and the paradoxical affirmation of reason that ensues.

Throughout The Geometry of Love, Visser appeals to love and reason in tension. They together point to paradox and contradiction, though contradiction is ultimately transcended in the revelation of divine love. In The Geometry of Love, Visser tacitly argues that the arresting construct present in her title derives from the resources and the affirmations of the Christian religion.

When reason submits to love, it flourishes.

Thank you for this link!

This documentary shares, distills, much of the meaning of the book https://www.paulcarvalho.com/geometry-of-love like this article.