Joyce Wieland was recently the subject of a retrospective at the Art Gallery of Ontario (AGO) in Toronto. I finally saw it over the holidays, though sadly I missed the opportunity to do so with Traces’ redoubtable editor. A Canadian, Wieland (1930-1998) split her time between Toronto and New York and was an activist and nationalist in the time of Pierre Elliott Trudeau. She worked with the materials of ordinary life, made a quilt of caribou that has hung in a Toronto subway station for decades, was an experimental filmmaker, and made installations of plastics and broken toys, often in the shape of 16mm film, frame by frame.

I determined to see her exhibit when I got a notice from the AGO with a blurb and a picture of a quilt with the words “Reason Over Passion” stitched into it. I assumed that, as a modern artist, she probably meant the phrase ironically. The title of the retrospective, Heart On, suggested as much, substituting as it does the heart for the head; I wondered what clues her other works provided, along with the curatorial explanations.

The description of the quilt threw me. Wieland was quoting Trudeau, who had recently said, “For many years, I have been fighting for the triumph of reason over passion.” The blurb observed that Trudeau’s words “intrigued her” and offered this explanation: “Concerned about the 1960s race riots and escalating war in Vietnam, Wieland saw in newly elected prime minister Pierre Trudeau (1919–2000) an answer to the United States’ increasingly violent and opportunistic imperialism.”

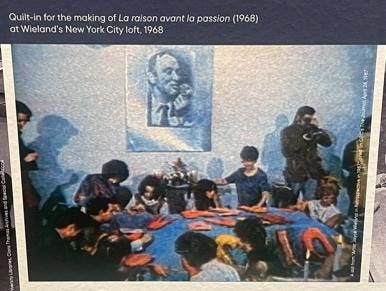

On this interpretation, passion means violence and the lust to dominate. Reason implies restraint and letting others be. We can extend the inferences. In May 1968 Wieland and her partner Michael Snow opened their New York apartment for a “quilt-in” that brought together about 100 people. Together, they produced the French-language version of the quilt, which the artist and her partner subsequently presented to the prime minister. Reason, then, in this context implies common sense, the collective judgement of the people.

A little digging revealed an alternative interpretation to the one of Wieland’s being “intrigued” by a politician’s phraseology. In 1969, Wieland produced Reason Over Passion as an 80 minute movie without dialogue but with the phrase “reason over passion” reproduced as 537 nonsensical anagrams. In the film, she sandwiches the footage she took of Trudeau at the 1968 Liberal leadership convention in between scenery she filmed from a road trip to the east coast and an earlier trip to Vancouver by train. The artist, looking to move back to Canada, declares that she “decided to unite the leader of the land [sic] and cement it with his words, not so much cement as spread them across a continent, reason over passion, overwhelmed, metamorphosed into passion through use.”

In one critic’s estimation, “[Wieland] became a propagandist whose work embodied an earnest declaration, but that by virtue of its intimate, passionate, irrational aesthetic, eagerly and gladly undermined that message.” For Wieland, this same critic avers, passion “seeps out of Canada’s green pastures and paved roads” and into “whatever eternal might remain glorious and free.” The website Quinzaine des Cinéastes agrees with this view. It holds that “as a woman, as an artist (who worked with textiles undervalued as women’s craft not high art), and as a passionate Canadian nationalist, ‘Passion over Reason’ described more of her own approach to art and life.”

Both of these views might be accurate, the one dating to 1968 and the promise associated with a new leader, the other to 1969, reflecting Wieland’s changing opinion of the federal government over time.

Nonetheless, what is one to make of this either/or? Both prospects will make the Christian uneasy. In many a Christian context, the call for reason to rule over passion is strong. The sentiment also reflects a Stoic ideal: freedom from the passions, what the Stoics called apatheia. A significant streak of Stoicism runs through Christianity (one would expect no less of a great moral system). Yet Christianity offers something more mysterious than Stoicism: a deepening of reason, utterly bound up with and dependent upon the revelation of divine love, which in turn gives (infinitely explorable) definition to love in the great scandal of particularity, the Incarnation.

The paradox of love and reason therefore also resists the artistic inversion of the Stoic paradigm. The contemporary Canadian artist will be grateful for the elevation of works by women, for the recognition of materials and forms once relegated to craft or the scrap heap, for the thrust of non-violence and ecological concern, all of which Wieland helped to effect. Yet the thoughtful person, let alone the Christian artist, can never rest easy with an “irrational aesthetic.” Such an aesthetic undermines itself the moment it opens its mouth.

In her silent, experimental record of the Canadian landscape, Wieland attests to a great presence and mystery. Neither these critics nor the curators apparently have the language to describe what her art helps to reveal, perhaps despite itself. Walking through the exhibit, I see virtually no signs of the artist’s wrestling with religious identity (except for the Spirit of Canada getting nailed by a bear and the sublimation of the religious impulse as a desire to reconcile politics and art). A metaphysically assured aesthetic beckons this generation of Canadian Christian artists, critics, and curators, one that looks to politics and art and to an “eternal” it dares to name, even as it acknowledges the inexhaustibility of its naming and its making.