Facing the Surrealism of James Tughan’s "Nine Faces of Christ": A Conversation

A Conversation between James Tughan & D.S. Martin

James Tughan is primarily known for being a visual artist working in visual mapping with chalk pastels. This work celebrates attachment to visible surfaces of the northern Ontario wilderness, but additionally to the less visible landscape of the human psyche, through a careful use of metaphor.

More recently, he has been drawn into the world of poetry, which has given him a way to articulate more directly certain aspects of these worlds: in celebration and lament, in overview and intimate touch. But then, the drawings have always been poetry.

James Tughan was interviewed by D.S. Martin over a series of email exchanges following the opening night of Tughan’s Nine Faces of Christ exhibition.

When my wife and I walked into Toronto’s RZIM gallery in the CBC Building in 2019 for the opening of James Tughan’s Nine Faces of Christ, I didn’t know what to think.

I had encountered the drawings of James Tughan through the years — through the Christian Arts organization Imago, through numerous pieces hanging in such places as McMaster Divinity College and Tyndale University, and through a feature in Image journal from 2018 — all of which gave me the impression of an artist whose vision ranged from realistic images of the natural world to the intriguing fantasy-scapes of his Dreaming of Lions series. I was ill-prepared, however, when we attended his opening for Nine Faces of Christ.

I am a poet, not a visual artist — not one experienced at drawing subtle meanings from an image. The meanings of a word can be found in a dictionary. Written allusions can be easily researched. Where might I find help in interpreting a drawing?

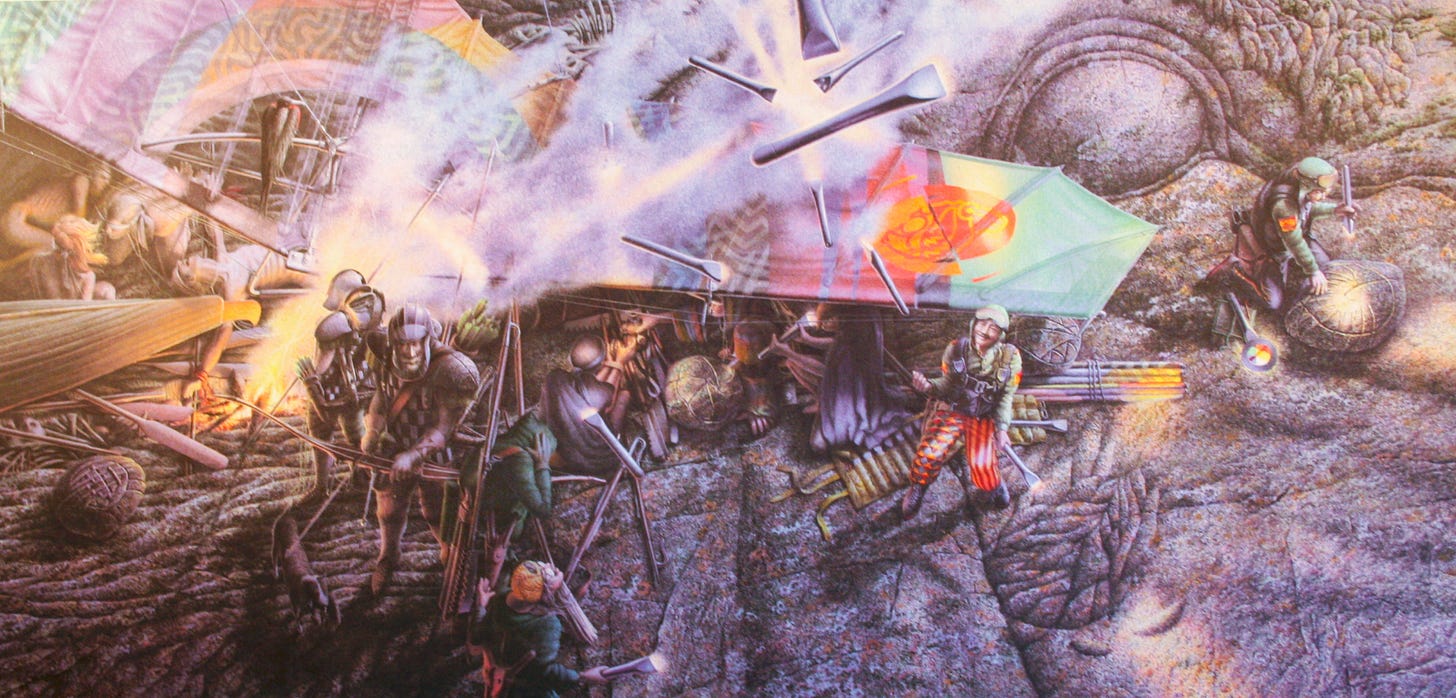

In Dreaming of Lions — a sequence of pastel drawings that takes up about 90 feet of running wall space — even though the images are other-worldly, what I see there seems to be like what I would see if such a fantasy world were to materialize in front of me. Tughan expressed in those days:

JT: In my work as a pastel artist, my adaptation of realism is what I call Cartographic Realism, a marriage of aerial visual mapping, natural symbolism and a Christian theology of the person. This style of imagery respectfully draws metaphors for the seen and unseen world of spirit from the natural surface topography of the visual subject matter itself.

In recent years, James Tughan and I have often met for coffee, but in order to focus his wonderfully rambling mind, I thought that a mutually-edited, back-and-forth email dialogue might best help me to elicit from James what has been puzzling me about Nine Faces. To communicate his history up until this point, James said:

JT: The Dreaming of Lions is a garden story, and like all imagery involving plants, what we don’t see before the early shoots raise their heads out of the ground, is all the inseminating variables in the soil and air that determine what we see later.

In my case this includes an upbringing in suburbia, evangelical Christianity, early toxic family life, architecture, Fine Art and theology education, wilderness canoeing, and global exposure in the Communication Arts as an illustrator.

One of my final assignments — during the time my career was focused on editorial illustration — was to draw gardens all over the USA for House & Garden Magazine. This project taught me almost everything I know about plants and gardens, which are extensions of their owners’ worldviews and domestic relationships.

My very last assignment was the Pinball project (1994) for the Ontario government, depicting the working conditions of artists in the industry I worked in. This project provoked me to leave the industry and work on subject matter that integrated the worlds of theology, art, and psychology.

I needed a way to depict more levels of reality than just aesthetics alone. I needed a realism that incorporated aesthetics, theology, and psychology, which together unpack layers of reality both visible and invisible.

This four and a half year drawing project began in 1997. It was added to with a third level of works, very recently in 2023. The purpose of this metanarrative study was to support Christians in their experience of trial and adversity, although it first began as my way of describing coming out of clinical depression.

James Tughan has been described by fellow artist Terry Black as “the leading artist in his medium, chalk pencil.” Black calls it “a merciless medium that demands discipline and labour.”

This, I can certainly appreciate.

James has frequently written poems to accompany his images. I selected eight of his poems for my anthology In A Strange Land: Introducing Ten Kingdom Poets (Poiema/Cascade, 2019) and one of his images, “Snagged,” for the cover art.

Perhaps what I encountered in the Nine Faces of Christ exhibit (in part) was a demonstration that, although I could interpret literally the scenes from Dreaming of Lions, I hadn’t engaged deeply enough with them to know what they are saying. I was only a casual viewer, appreciating the skill involved in producing them.

The problem I faced when viewing Nine Faces of Christ was that they didn’t seem content to have me as a passive observer. Now that I was viewing Nine Faces, their surrealistic quality left me rather lost at sea.

In his beautiful new book Contact: The Artistry of Jesus in Nine Faces (Nadir Publishing, 2023), written to accompany his drawings, Tughan presents to us a new way of looking at Jesus of Nazareth: that is, to see Jesus as an Artist. To get at this, I asked James what evidence he would give to the skeptics to demonstrate that Jesus is indeed an artist. He responded:

JT: There are several stunning indicators of this. The first is scripture itself, which, beginning with John 1, clearly aligns the logos —“word” — with Jesus as the most visible architect of Creation.

This is echoed in the repeated signs of the extreme creativity of God interacting with humankind, and our constant meanderings from truthfulness: the theophanies, his myriad responses to Israel’s descent from theocracy to captivity and back, and especially the imaginative and perhaps revolutionary ministry of Jesus to individual persons and institutions. I also believe that the language elements of art that visual artists work with daily in their design and craft practice can be shown to exist in the work of Jesus.

In Nine Faces, I try to show how those elements at work suggest that Jesus is thinking like an artist all along, (in the chapter called ‘Incarnation’) as he tries to recover his original handiwork. We have theologians like N.T. Wright to remind us also that since the resurrection, He is continuing the process of restoration, in spite of our catastrophic shortcomings.

I then revealed my vulnerability as an Art appreciator to James:

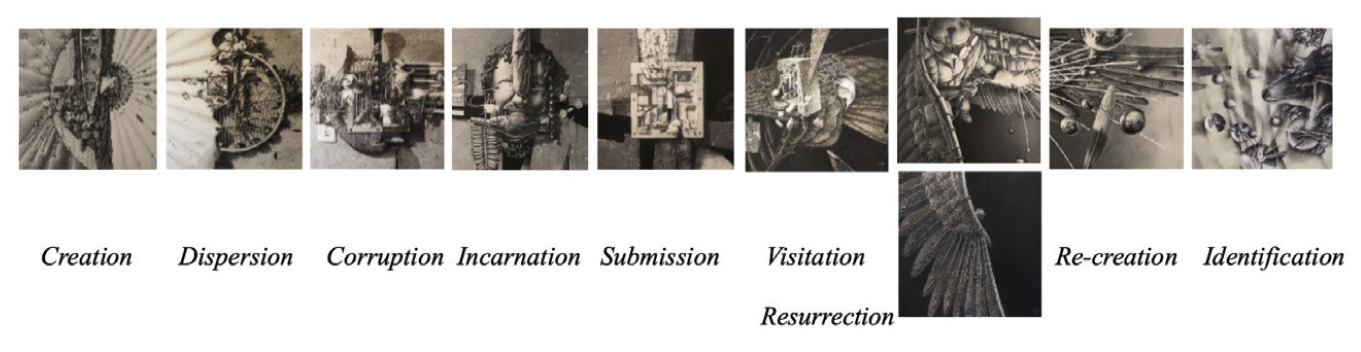

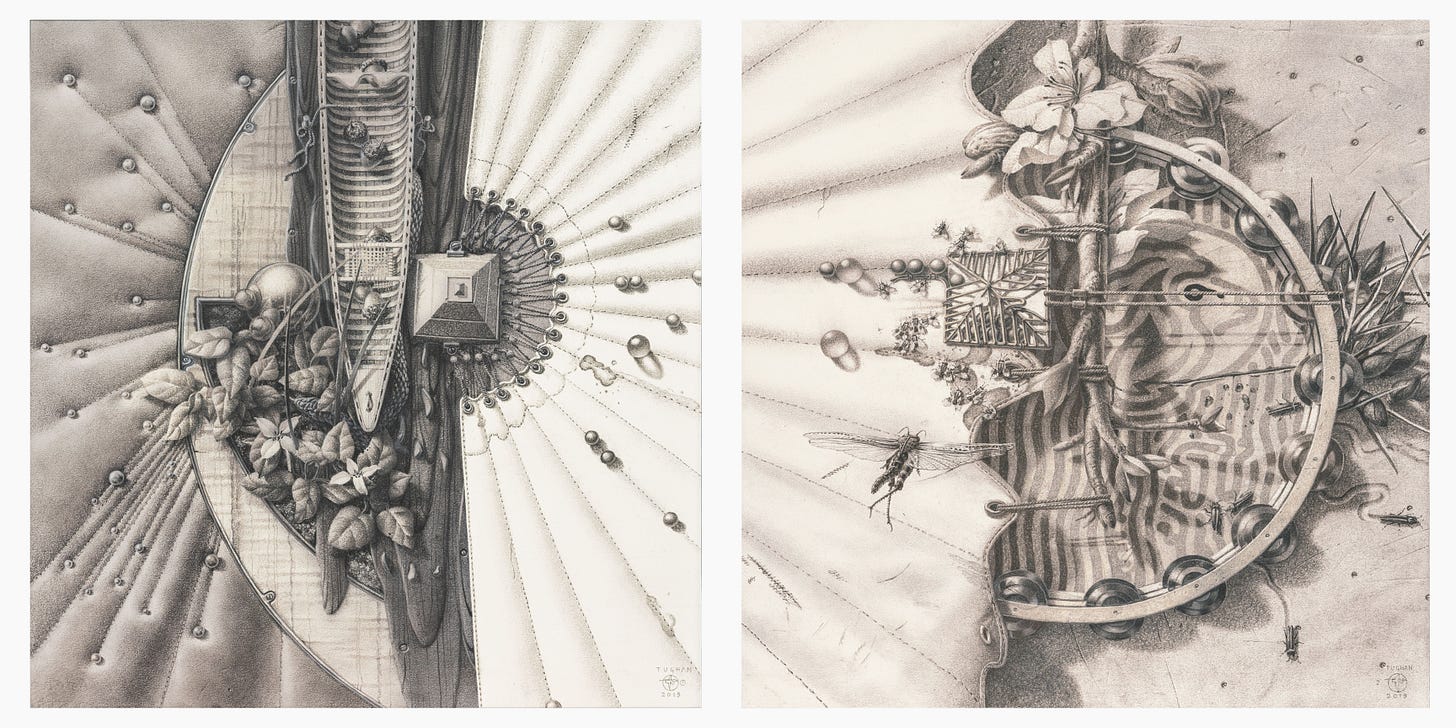

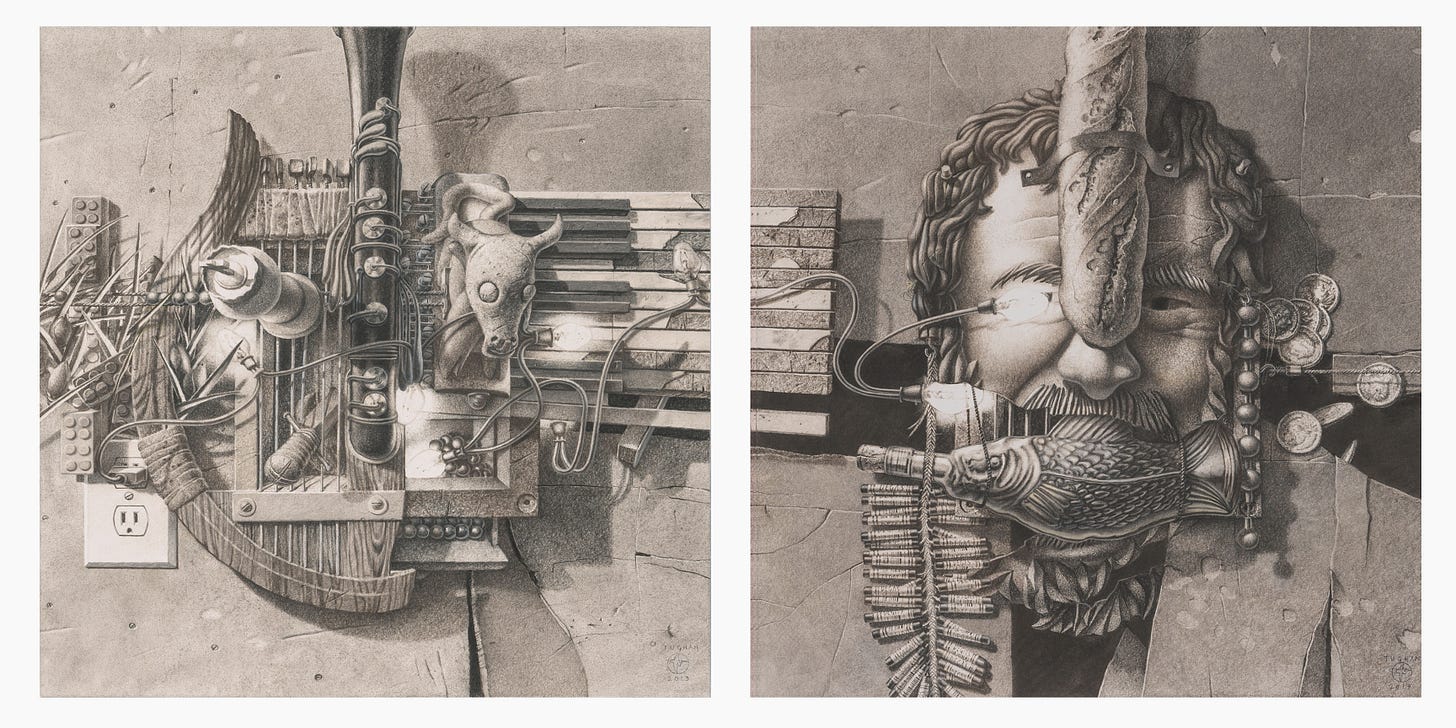

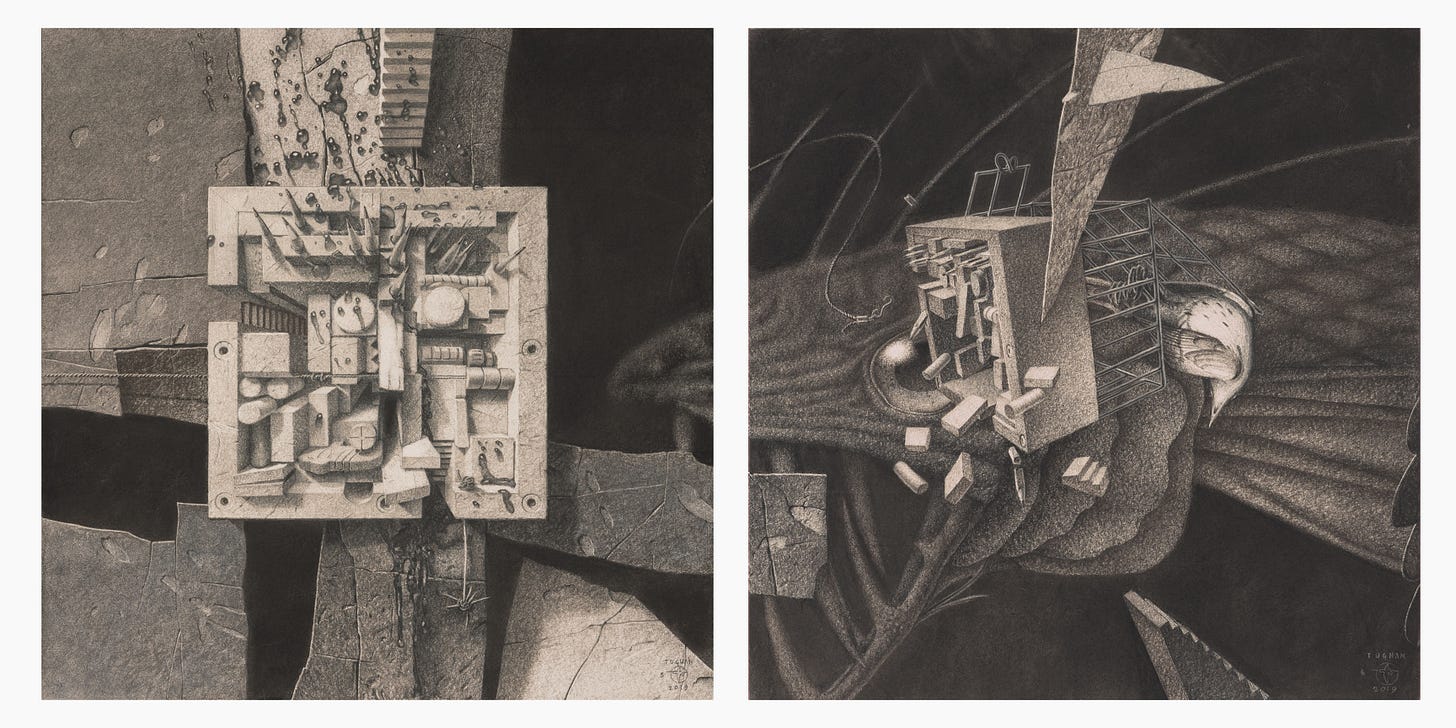

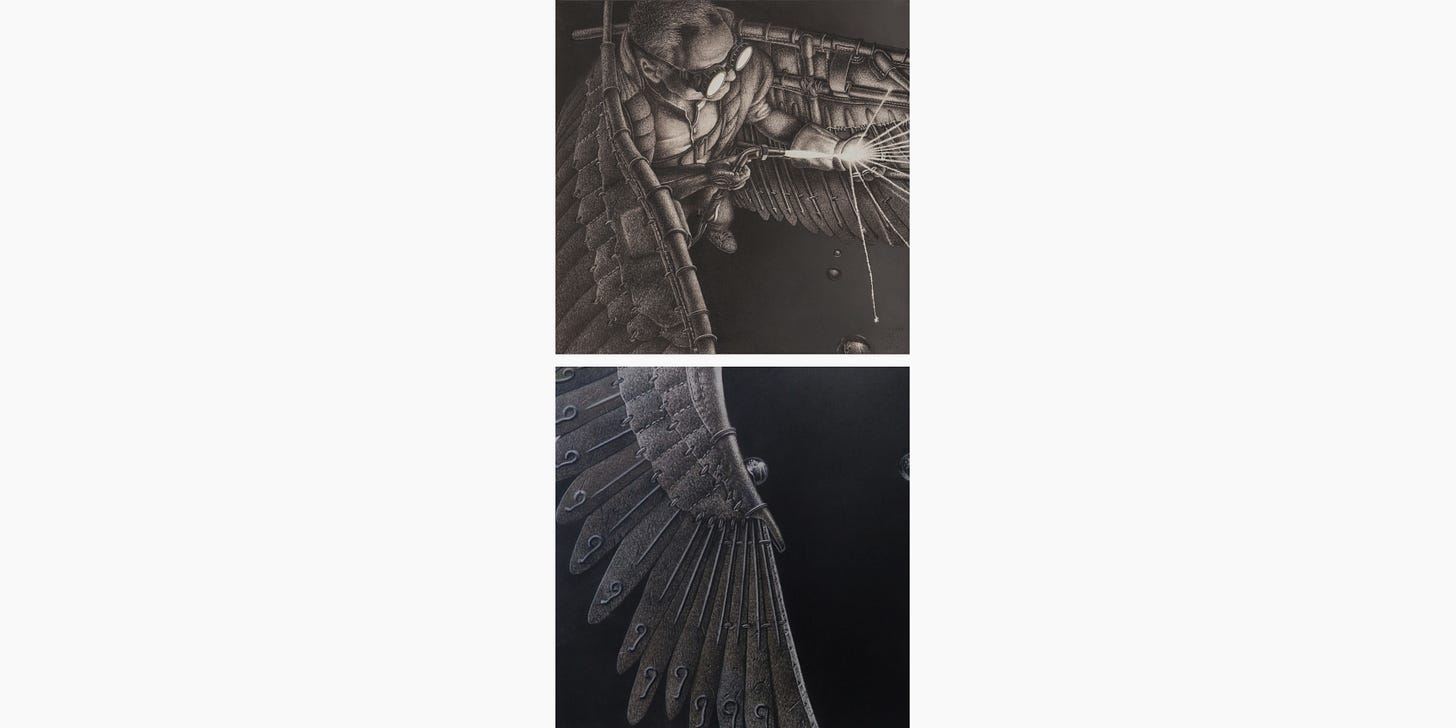

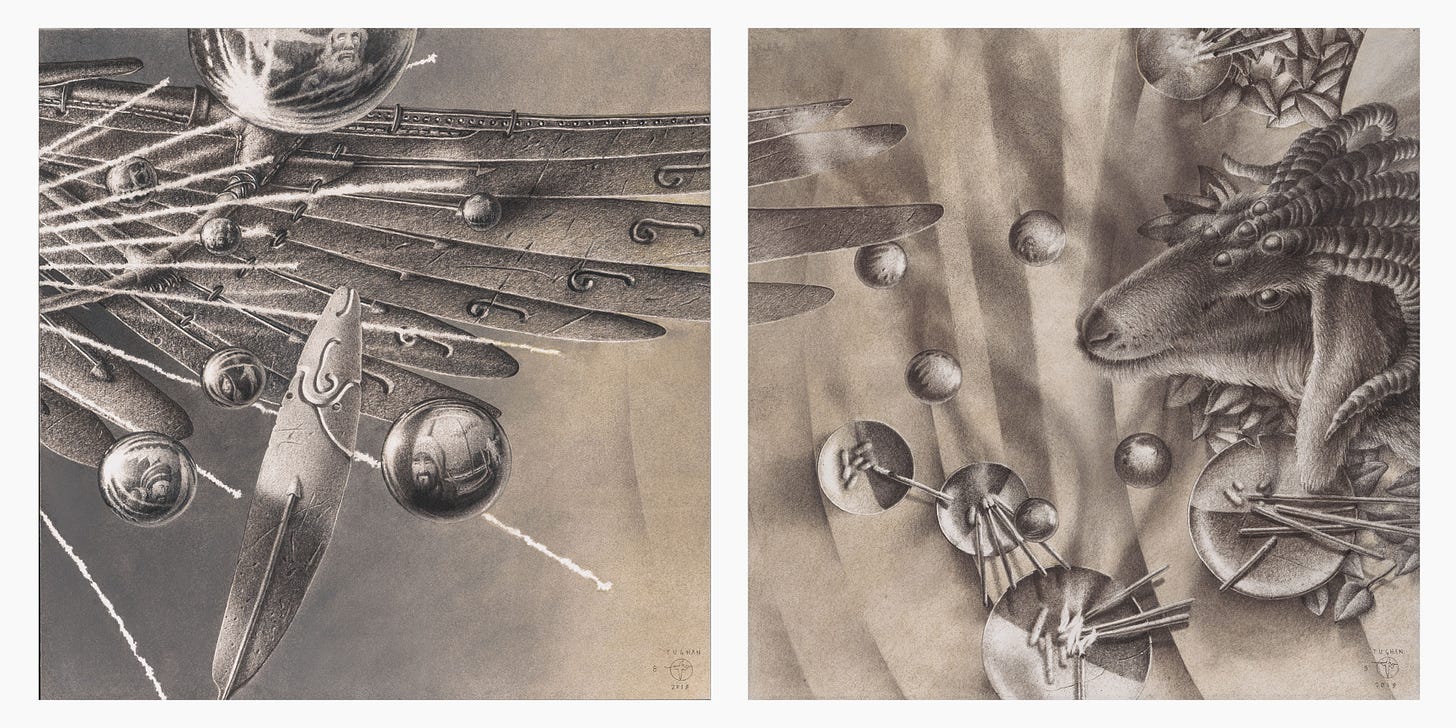

D.S.M: As I look at the nine portraits in your drawing series, The Nine Faces of Christ, James, I see faces... sort of; that is, I see images with objects positioned to suggest faces, with the title Nine Faces prodding us to try to see them as faces. In ‘Creation’ a canoe suggests a nose; in ‘Dispersion’ the circle of a tambourine makes us see it as a head; when we reach the fourth picture ‘Incarnation’ there is definitely a face — one that looks like it might even be your own self-portrait but with a baguette affixed to the forehead with a small clasp and finishing nails, and with a fish-wrapped wine bottle shoved sideways into his mouth. These obstacles make it hard to know for sure.

James (I think patiently) responded:

JT: Nine Faces is a surrealist narrative about a descent from creative freedom into betrayal, legalistic bondage and then resurrection again to concrete reunion with the original artist and real hope of restoration.

Each of these images are nine different portraits of Jesus, surrealistically made up of objects, whimsically portrayed as scientific collages, while the background slowly disintegrates and is replaced by Jesus portrayed as flying welder. There is a lot of tongue in cheek playing around with biblical metaphor, which I think may be useful in our community that makes theology so incredibly serious. Some of that trompe l’oeil treatment of metaphor comes out of my own life, some from Old and New Testament history.

The Incarnation references are not to myself, but to someone wearing a plastic party mask (look closely) in a piece that has everything to do with Israel’s attempt at an ultimate misappropriation and containment of the Messiah promise.

And so, I asked James to tell us about his approach to making meaning in this series as a whole, and how we as viewers are to approach it.

JT: The whole sequence might be best appreciated by persons more familiar with scripture, but there is another progression of structural metaphor from curvilinear forms to box-like, angular containment and then explosive freedom, that really is most recognizable to persons betrayed by various kinds of trauma.

This imagery was designed to not be obvious, but imaginative, playful and thought-provoking, just as Dreaming of Lions asks us to see a God-like character in a harlequin juggler, and Godspell portrays him as a baseball yard street clown. I think what artists are called to do is refresh shopworn metaphors while still continuing the core truths God has himself put to us. This is something Jesus also did by the well. Take for example references to bread, water, the Passover lamb, the temple references and his reworking of Moses’ brass serpent and Jesus’ cross. (This is an artistic device of rhythm and referential metaphor.) This parable-like imagery was designed with the viewer’s intelligence, imagination, and sense of humour in mind.

Spoiler alert: There is one more device involved, that is more obvious perhaps in the real physical installation than the book, but has to do with the station point (where the viewer is standing relative to the imagery). This also is a trompe l’oeil way of involving the viewer in the story. This book also ultimately reminds us of Jesus’ artistry in making contact with us individually, speaking in terms that respect and challenge our individual value in Creation.

I believe that what’s needed for someone to make a poem their own, is to spend time reading it carefully, drawing insights from it, and discovering the ways it resonates for them — similar to how we draw meaning from scripture. I’d even go so far as to say that a poem isn’t a poem until it is read. What’s needed for us to make a work of visual art our own, I suspect, is quite similar. I wondered what James might say to this.

JT: Yes, every visual artist, in whatever stylistic language they are working in, whether they admit it or not, is working to seduce the viewer (spatially) into the world they are imagining. It can be renaissance realism or post-modern abstract expressionism. We want people to come into this world and walk around, to engage the mystery of these spaces and colours.

In the case of work with known or less familiar symbols, there is another kind of play going on with associations and recollection of reasoned ideas. There is a playfulness possible with the rational side of how we engage the world around us as much as the purely aesthetic.

The viewer is, in point of fact, being asked to do some work, in the same way Jesus’ parables ask his sometimes confounded disciples to think with their hearts and minds at the same time. In the case of Nine Faces, what you discover is the experience of overcoming trauma with creativity.

D.S. Martin is Poet-in-Residence at McMaster Divinity College in Hamilton, Ontario, the Series Editor for the Poiema Poetry Series from Cascade Books, and serves on the Advisory Board for Traces. His poetry collection The Role of the Moon is forthcoming from Paraclete Press.