Afternoon at the beach

3:45pm on a May afternoon in a coastal city. An aspiring playwright from the prairies, Vanessa has just learned her first script will be produced. Exultant, she walks by a beach, and watches an old sailor, Enoch, playing with his young son after school.

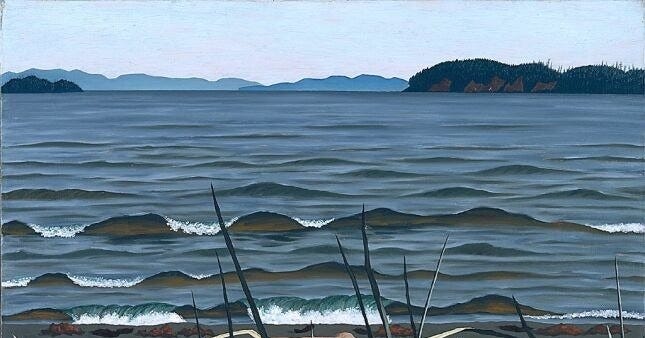

Vanessa skips south to the waterfront to feast her eyes on the wheat-like waves — slips off her Vans to walk the wet sand discalced. Prostrate waves adore her soles, their chill labia licking gooseflesh up her legs. She hums country songs from home about love “higher than the pine trees growing tall upon the hill,” worries why she doesn’t feel like that, and maybe never will. Enoch and Samson watch crows pick through ficus tide rows for tidbits. The sand’s bleachers of stranded logs are occupied by off-work ESL instructors passing flasks from fist to fist, ogling Vanessa as she treads the ocean’s lip with lilac flats dangling from pink fingertips. Jeans rolled up, father and son footrace in the greasy surf like Achaeans, skip stones like little boys. When driftwood floating in the shallows is revealed as a dead seal, Samson’s appalled, but Enoch rolls the corpse by one rubbery flipper until he sees red seeping through the silver pelt. See this? Enoch says, pointing at the bullet hole, Some fishing boats still carry shark rifles to cull seals, afraid they’ll steal salmon, rip expensive nets. Moved by pity, Samson rests his palms on the fur and tests the whiskers on its upper lip with childish fingers. Enoch nods his approval, recites words he lived by long ago: Most would rather judge by sight than by the touch; for everyone may look, but few may touch and feel; all can perceive an appearance; few can grasp what really is. Samson is agog: his father never speaks like this to him. Watching father and son from the tideline where she stands, Vanessa’s eyes sting with a need for meaning and she gasps when they stroke the seal as sad children stroke dying dogs goodbye while a vet preps the fatal shot. Soft saltchuck pulsing in ripples around the trio and her own fingerprints prickling like battery contacts in a charger, Vanessa rethinks energy and transformation in her play, wonders if Viró can devise special effects — clouds, flames, winged things unfolding into being when a flap is flipped like pages in a pop-up book. Enoch and Samson solemnly strip to skivvies, wade into surf with the buoyant body towed between them, then swim side-stroke until the tidal rip accepts their gift, drags it from their grips. The water transmits Enoch’s homily to the shore as they swim back: Going to the sea… The neatest, cleanest funeral in the world, except it’s free. When it’s my time, I hope you wrap me up with stones to help me sink, send me down to the crabs to pay my debts for all I’ve taken out by line and net. Vanessa makes a mental note of the old man’s words, and again, as man and little boy huff and puff in the shallows, stumble and shiver up the sand, she notes the schematic of muscle and bone they share, one version waning and one waxing.

Daniel Cowper’s poetry and critical writing has appeared in numerous publications in Canada, the US, Ireland, and the UK. His poems have been collected in The God of Doors (winner of the Frog Hollow Press Chapbook contest) and Grotesque Tenderness (MQUP, 2019). His latest work is Kingdom of the Clock, a novel in verse about urban life. He is a contributing editor with New Verse Review, and lives on Bowen Island with his wife Emily and their children.

Lovely. Enoch and Samson are both the names of Cree bands in Alberta. Coincidence?