Ernest Hemingway has a reputation for being a gruff writer with a spare style. It would seem unlikely, then, that he would deploy something clichéd, if not sentimental. Aren’t we fast perceiving that those possibilities could pose a problem for love-and-reason-in-tension?

You say tomato, I say tomato. In the arts, a convention is a requirement, establishing expectations and holding forth the promise of some sort of revelation in the hands of an artist… until it becomes hackneyed and conventional. Courtly love had conventions, like love at first sight, that eventually became conventional. Detective fiction has conventions, like the incompetent police, that have become conventional. Love and reason in tension is a convention, but its resources run deep. They lie somewhere beyond convention; love-and-reason-in-tension is elemental.

In The Old Man and the Sea, there are relationships (with the potency of love) and there are techniques (expressions of reason). But there’s nothing like a tension between head and heart at play at all. Nothing on the horizon, nothing in the offing. Until suddenly it appears in the story’s climax.

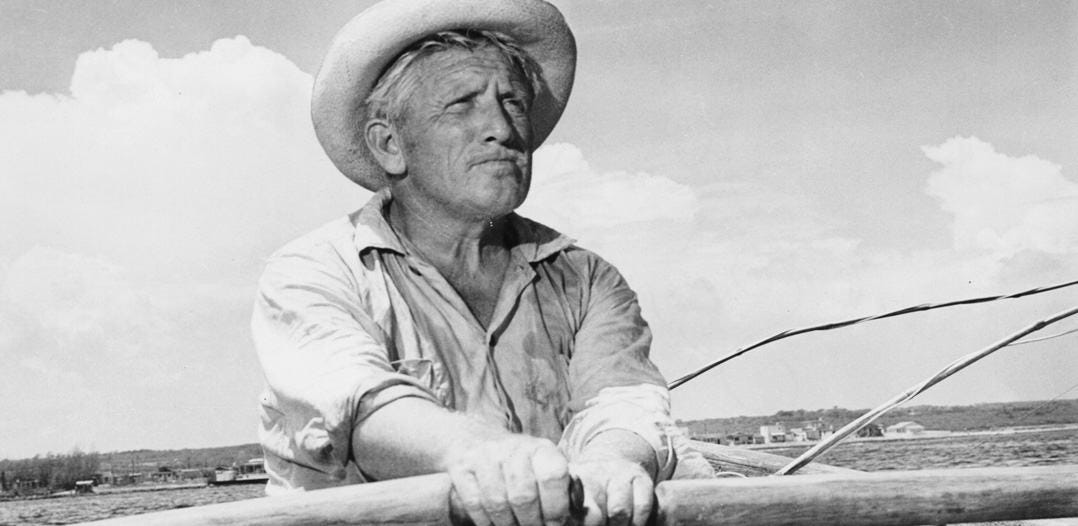

It’s all so Hemingway: a random day in the life of an old man with whom we sympathize, partly because apparently his best days are behind him, partly just because we’re with him. To borrow the idiom of this kind of story: there’s this guy, and he’s going fishing like he always does. He gets up early and puts his boat in the water with the help of some kid. Then he’s off, all on his own. Whatever. If I sound like one of Raymond Carver’s narrators or Jesse Pinkman, that’s because they stand in this literary tradition.

The old man is vaguely hoping for a big catch: “I worked the deep wells for a week and did nothing, he thought. Today I’ll work out where the schools of bonito and albacore are and maybe there will be a big one with them.” Later we read, “Now is no time to think of baseball, he thought. Now is the time to think of only one thing. That which I was born for. There might be a big one around that school, he thought.”

He goes out far and the day gets late. If we know anything at all about the story from its massive reputation, we know this. If we can remember that state of innocence when we didn’t know what happens: we are dreading the crisis that is surely coming when he’s out too far, not the dissipated loss after his surprising triumph.

Hemingway reveals that loss exquisitely. He leaves the reader with complicated feelings of pain and ambivalence because we don’t stop relishing the old man’s victory and don’t simply set it against the pathetic trip back like a mockery.

Hemingway casts this triumph, with its enduring lure, in terms of a dynamic tension between the head and the heart. Nothing prepares the reader for the use of this language and it disappears as quickly as it surfaces. For a few glorious moments, though, we confront it in the climax of the battle between the old Cuban and the marlin he has tracked down. In fact, the appearance of the convention is the climax, the ordering of head to heart, the event of the story.

The old man has had the fish on his line for some time. Finally, he sees it and he can’t believe its size: “He saw him first as a dark shadow that took so long to pass under the boat that he could not believe its length. ‘No,’ he said. ‘He can’t be that big.’”

He knows that he is “gaining line” and that soon he will have the chance to harpoon him: “But I must get him close, close, close, he thought. I mustn’t try for the head. I must get the heart.”

The fight continues. He sees that “the fish’s back was out,” that he’s higher in the water. We see the readied harpoon, the coil of light rope in a round basket, the way it is fastened “to the bitt in the bow,” a taut piece of alliteration reinforcing the tightness of the knot. The fish straightens and circles. The old man is pulling, his legs braced. He’s praying for a clear head after a day of hunger, sunlight, and thirst:

Now you are getting confused in the head, he thought. You must keep your head clear. Keep your head clear and know how to suffer like a man. Or a fish, he thought.

“Clear up, head,” he said, in a voice he could hardly hear. “Clear up.”

Then he is thrusting the harpoon down with all his strength, feeling the iron go in, leaning on it with all his weight. He sees the fish rise out of the water “with his death in him,” seem to hang in the air, then fall with a crash:

The old man felt faint and sick and he could not see well. But he cleared the harpoon line and let it run slowly through his raw hands and, when he could see, he saw the fish was on his back with his silver belly up. The shaft of the harpoon was projecting at an angle from the fish’s shoulder and the sea was discolouring with the red from the blood of his heart.

Both fisher and fish are wholes, made up of head and heart. The old man recognizes the heart as the necessary target and in that moment reveals his own passionate savvy. Together, fisher and fish make up another whole as big as the sea and the sky. In it the old man represents the head and the marlin the heart, and the fish triumphs over the fisher.

Like the sea and like getting old, the tension between head and heart is elemental. Hemingway’s appeal to it serves to elevate the story to the status of myth. Like Sophocles, Hemingway writes with mythic economy. Head and heart here belong to a vision reduced to essentials that are anything but reductive.

The trope of head-and-heart-in-tension is personal and subjective in the sense of subjectivity Meister Eckhart described when he wrote these words:

Among all things there is nothing so dear or desirable as life. However wretched or hard his life may be, a man still wants to live. It is written somewhere that the closer anything is to death, the more it suffers. Yet, however wretched life may be, still it wants to live. Why do you eat? Why do you sleep? So that you live. Why do you want riches or honors? That you know very well; but – why do you live? So as to live; and still you do not know why you live. Life is in itself so desirable that we desire it for its own sake.

The fish’s triumph is to represent life. The old man keeps his head, but the marlin tinctures the sea with his blood: “The sea was discolouring with the red of the blood from his heart.”

The convention bears the impress of the writer’s style. It might seem commonplace elsewhere, even sentimental. Hemingway accepts the risk. He achieves something revelatory in rising to the challenge. As always, the artist bends to the convention; in a good story, the convention, even an elemental one, bends to the artist as well.