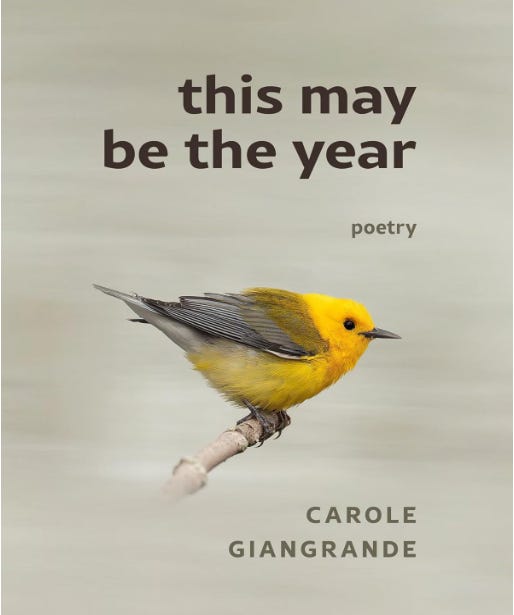

This May Be the Year by Carole Giangrande (Inanna Publications, 2025)

Reviewed by Mike Bonikowsky

She loves the world she sees, and because she loves it she is afraid.

When I was young, I used to write poems almost every day. Everything I saw inspired me. Everything I felt, I wrote down. Around every corner some new sight or feeling or experience would grab me and inspire me to write a few lines about it. I felt it so strongly that I was likewise assured that others would want to read these poems, so I would share them, submit them, publish them. I wrote poems like a bird sings, at least in regards to volume and frequency.

I don’t do that anymore. As I get older and my life slows down and the new experiences that used to inspire me become fewer and farther between, so too has my poetic output slowed. The big events of my life have already occurred and been duly chronicled in verse. The things I see and feel I have seen and felt before. Those poems, I tell myself, have already been written. Nobody wants to hear it again.

“This May Be The Year”, by Carol Giangrande, is a much-needed reminder that I am wrong: Wrong about how I see my life as I enter its second half, wrong about the function of poetry.

Giangrande writes poems about everything. She writes poems about getting her hair cut. She writes poems about what she sees on the news. She writes poems about dead friends I will never meet. More than anything else, she writes poems about birds. Her sharp, staccato free verse, never more than a few stanzas long, cries out like birdsong in all its forms. There are dawn-choruses here, and evensongs. There are cries of pain, many of them, that cut through the silence like the scream of the red-tailed hawk. There are little hymns of anger and of loss. There are celebrations of the everyday, and chilling portents of the end to come. In the titular poem, which describes the failure of the natural order as symbolized by a mother hawk seen on a webcam who has failed to lay an egg:

Online,

Around her head, an aureole of sun,

Feathers darkening the wide screen

Body large with waiting for whatever comes.

Not every bird-poem is an apocalypse. Most are just encounters with birds Giangrande has clearly loved and been moved by the sight and sound of, not earth-shattering experiences with rare birds, but just ordinary birds doing the ordinary things that birds do. As her truly lovely self-description by the titular bird in “Kingfisher” concludes:

My eggs are sunlit, my young a dazzle

Of longing and hunger. Each spring breaks open

Into summer’s ripening. Then and now,

My wings are streaked with sapphire rain.

My body is silk on the wind.

In reading these poems, it is made overwhelmingly clear to me that Giangrande is wiser than I am. In this collection, Giangrande shows me what I have forgotten: There are no ordinary birds. There are no ordinary events in a human life. Every bird, every person we meet, every day in every life, is a miracle. Every bird contains within it the whole of the sky. Each piece is an irreducible part of the whole. Poetry is not the capturing of the extraordinary, but the natural human response to the true reality of the human experience. It is the absence of poetry that is unnatural, extraordinary. We are meant to make art as the birds sing: constantly, naturally, unconsciously. It is part of our function. We are meant to live as the hawk she describes in “Rusty”:

He lives in the grip of his soul’s needs;

food, nest, and safety,

gives me his presence,

gift enough.

Giangrande knows that the moment is all we have, that the rest is an illusion. We, no less than the birds, are given our daily bread and no more. In a sense the birds she sees are her daily bread, her little ration of beauty to sustain her in the grey and dying city that serves as the backdrop for so many of her poems. Giangrande has the gift of recognizing and accepting her ration, and then fulfills her poet’s vocation by transubstantiating it into something that can sustain her audience.

The poems that comprise the first part of the book, entitled “Birdmind,” celebrate beauty and anticipate heaven. The next three sections, “Breath of Ghosts”, “Memory’s Shadow”, and “In The Long Grass,” provide contrast by sinking deep into the grim and grey world of humanity. They are primarily poems of mourning: Mourning a presence that should be enough but never seems to be. Mourning for dead and dying friends. Mourning for the natural world and the violence visited upon it. Mourning for the fatal bent of history.

There are poems about mass shootings, about the Covid-19 pandemic, about the long shadows of the Holocaust and 9/11, about sexual assault, and the Syrian civil war. Birds fly in and out of nearly all of these scenes, although they are no longer the focus. They are there, high above, still singing, reminding us of what we have forgotten, how we got into this mess, and maybe how we will get out of it again. There are hints of hope here, but only hints and only for those with ears to hear and eyes to see, as in the final stanza of “Red-Tails Over Gotham”:

How they care for their young,

Nestle them close against the night,

Cries of the enormous city

Stilled under their wings.

Christ, the mother-hen is here, among the hawks, gathering Jerusalem under his wings, if we can see him. But that is no guarantee.

If I could take fault with any aspect of Giangrande’s collection, it would be this scarcity of hope, the air of fatalism that infuses most of the poems. While it is less present in “Birdmind,” it seems to grow as her focus leaves the birds and settles on the world around her. The birds in her poems are free because they cannot look beyond “the grip of their soul’s needs,” to use her lovely phrase. We are not so lucky. We are cursed with understanding, with the knowledge of good and evil. The best we can hope for, Giangrande seems to say, is to temporarily forget ourselves in imitation of the birds, a brief holiday from the anxiety that is our true and natural state. As her collection ends in the final stanza of “In The Long Grass,”

Four million years before the sun goes out.

Today we rest in the long grass.

This is a chilling note to end on. I, as I am today, find myself longing for another word, another coda from her, something with more hope than this. Perhaps this is because I see so much of myself in Carole Giangrande. She loves the world she sees, and because she loves it she is afraid. She sees the end coming, and she is not wrong. She is trying to keep one eye on the birds, and one eye on the news. But the birds are miracles of subtlety, and the news doesn’t play fair, and it is clear which is coming to dominate her inner eye. I can’t judge her for this, for I have had the same experience. It is to Giangrande’s credit that she does not invent what she does not observe herself, and I applaud her courage in staring into the abyss, but I find myself wishing the seer had read brighter portents in these dark days. This is my weakness, however, not hers.

What Giangrande does see and understand and makes her thesis, is that to be human is to make art as a gift to others, of one kind or another, even if that art is just the effect of our presence on the mosaic around us. The poems in This May Be the Year are by their very existence a call back to this essential function of humanity, one I personally very much needed to hear. We do not make because we are paid to do so, or because we have been given the title of artist, or because we have been given a platform to do so, or because our Voice is Important. We make because we are not fully human unless we are doing so, as the birds are not themselves without their song.

Carole Giangrande has given generously of herself in this collection, of her joy and pain. She has held nothing back, and if nothing else I feel that after my time spent with this collection I have come to know a human being I did not know before, and that in and of itself is priceless. Giangrande has fulfilled her vocation as poet, and inspired me to do likewise. She has kept the promise she makes to the bees, and to us, in “Worker Bee”:

I tell them I will try my best

To bring them joy…

That I am only a helper,

That the round world ripens like a berry, even

In the midst of death,

That we hover inside

The same mysterious hope.

Mike Bonikowsky lives in Dufferin County, Ontario where he works as a caregiver. He is the author of Red Stuff and The Shepherd of Princes, both published by Solum Literary Press.

Carole Giangrande was born and raised in the New York city area, and came to Canada to study at the University of Toronto. She’s worked as a broadcast journalist for CBC Radio, a Writer-in-Residence and as a teacher of journalism and political science, and she’s given readings at Harbourfront, Hart House and the Banff Centre for the Arts. Her fiction, articles and reviews have appeared in Grain, New Quarterly, Descant, Canadian Forum, Matrix, The Globe and Mail, The Toronto Star and Books in Canada. Her poetry has been published in Queens Quarterly, Grain, Spiritus, The New Quarterly, Braided Way, Mudlark and Prairie Fire. Her essays have appeared in Eastern Iowa Review, EcoTheo Review and Antigonish Review. She’s married and lives in Toronto where she enjoys birding and photography.