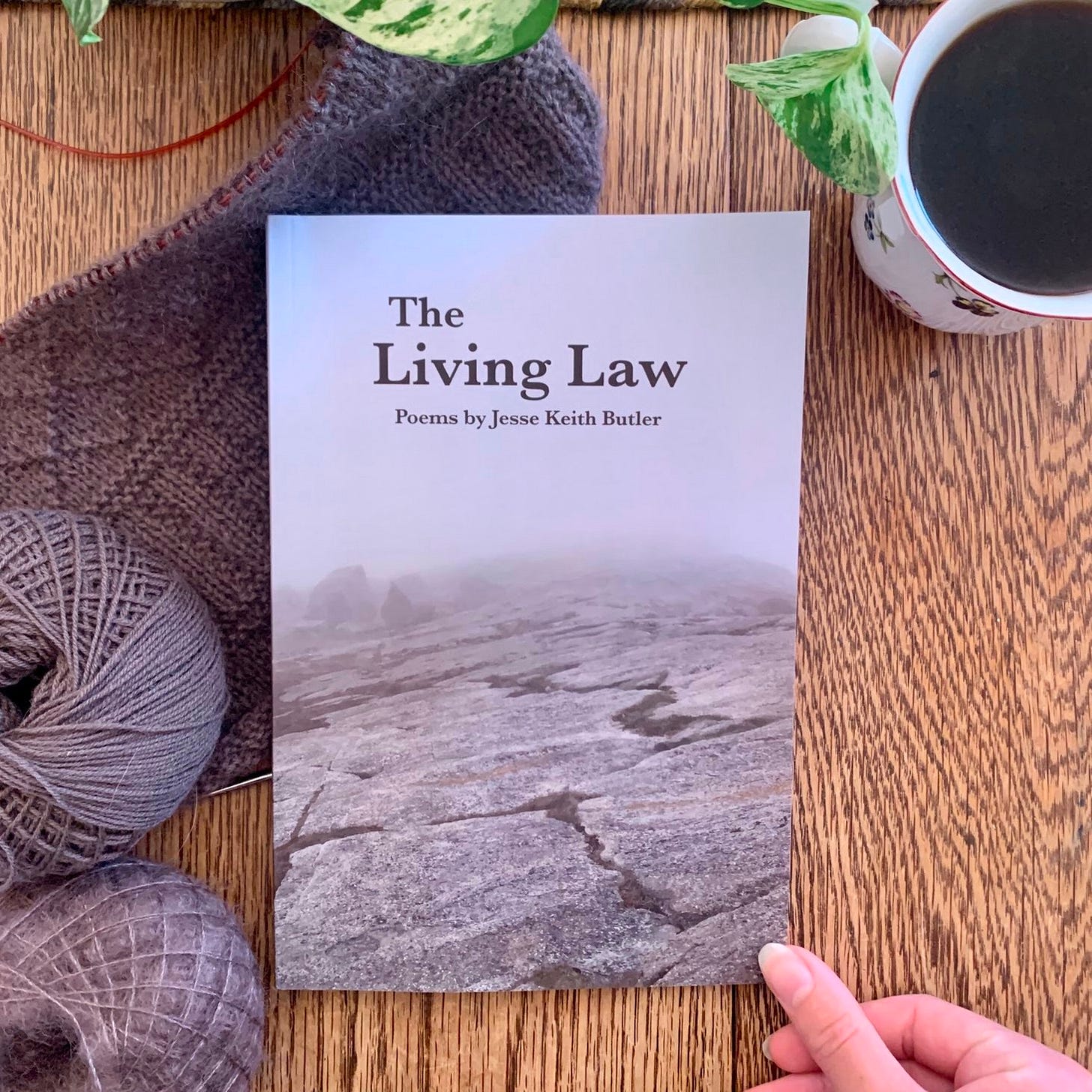

The Living Law by Jesse Keith Butler (Darkly Bright Press, 2024)

Reviewed by Steven Searcy

In life, as in poetry, our paths are always constrained—by outside forces and by our own choices. To choose one direction is to reject an alternative, even if we seem to be taking an approach that is more free and uninhibited. We must either submit to the constraints of our own desires or look to an external framework to guide our path. But much of our culture’s stance is to view any constraint as a threat to freedom. Limits and traditions are for puritans from backward societies of the past, says conventional wisdom—or, in the words of Elsa from Frozen: “No right, no wrong, no rules for me—I’m free.” Against these postmodern headwinds, Ottawa-based poet Jesse Keith Butler offers a very different type of liberating message:

The law has life. It’s more than normative.

It is a gateway, opening to offer

a wide abundant space in which to live.

Butler explores this theme throughout his debut poetry collection, The Living Law. In a recent interview with Brian Brodeur in Literary Matters, A. E. Stallings noted, “Constraints are freeing in themselves, […] as formal poets and avant-garde poets tend to agree. They free you from feeling that you are entirely in control.” Butler’s work illustrates this truth through both the subject matter and the use of poetic form, pointing toward a deeper kind of freedom that can be obtained by submitting to limits beyond oneself, instead of the superficial “freedom” of following one’s own fickle whims. These finely crafted poems cover road trips across Canada, a night of whiskey drinking with a buddy in an old church belltower, the joys and agonies of parenthood, and the inner lives of the Biblical patriarchs. Throughout, Butler renders relatable human experiences while displaying a strong grasp of the capacities and opportunities to be found within the limits of traditional English metre and rhyme.

One exemplary highlight is “Lightning Strikes Churches,” which was selected by Dana Gioia and Mary Grace Mangano as the 3rd place winner in the Kierkegaard Poetry contest (appearing in the Homage to Søren Kierkegaard anthology from Wiseblood Books as well as Dappled Things). Use of the refrain “When lightning strikes churches” in each stanza necessitates four different end rhymes for “churches”—but rather than limiting the poem’s effect, this constraint yields striking imagery, including pigeons that “burst from their perches / and soar in the churchyard’s blank sky,” and a ship that “leaps and lurches / then leans to the unsighted shore.” The poem rolls through symbolically charged images that simultaneously offer a harrowing challenge to spiritual pride and complacency as well as a stark beacon of refuge and hope for the humble.

“Lightning Strikes Churches” demonstrates Butler’s fine ear for the music of language, conveying meaning through the sense and sounds of the words. Many of the poems in this collection beg to be read aloud, and this one is no exception. Here is the third stanza:

A church is a monument, far out of fashion,

that clings to the crumbling brink of the land,

a ritual built between Isaac’s cold question

and Abraham’s trembling hand.

When lightning strikes churches

it surges with light

and restlessly searches

for faith formed unbent in the night.

Also “far out of fashion” is the poem’s use of trisyllabic metre (amphibrachic or anapestic, depending on how you prefer to scan), which has become rare in contemporary poetry but figures prominently throughout The Living Law – around a quarter of the poems in the book use some type of strict or loose triple metre.

While the iamb has long been the dominant pulse in English poetry, over the last century the trisyllabic feet were further demoted, being largely consigned to the realm of light verse or inextricably linked to passé styles from prior eras. Butler shows no qualms employing triple metre in highly serious poems, including the title poem which kicks off the collection as well as “Lightning Strikes Churches” and “Villanelle of the Elect.” Many of these trisyllabic poems that tackle weighty material retain a gravitas through judicious application of metrical variation: “The Living Law” has an iambic refrain at the end of each stanza, “Lightning Strikes Churches” uses mixed lines of tetrameter, trimeter, and dimeter, and “The Lawgiver” is based on a loose tetrameter with significant metrical variation and substitution.

While the use of trisyllabic metre is noteworthy, Butler also displays skill across a variety of other metres and forms. “A Strand of Sound” and “The Red Sun Rising” use fourteeners (iambic heptameter), another “anachronistic” form that can prove effective in the right hands. There are also plenty of conventional iambic poems, including several Petrarchan sonnets. Butler even sprinkles in some free verse and prose poems, which provide nice variety—though it’s clear the more formal work is Butler’s wheelhouse. His use of rhyme is also nimble, both as he employs prudent slant rhymes and when he sticks to true rhyme. Though most of the book is unabashedly written with regular rhyme and metre, the frequent use of bespoke nonce forms lends a freshness to the work, and sometimes even hides the complex formal structures that undergird many of the poems.

“The Lawgiver” exhibits such intricate layers of form and meaning, and is worth noting as the longest poem in the collection. In addition to the loosely anapestic metre mentioned above, it also follows a relaxed rhyme scheme (axxa) and makes ample use of alliteration, gesturing toward Anglo-Saxon alliterative verse. Separated into twenty-two sections arranged as an acrostic on the Hebrew alphabet, it mirrors the structure and content of Psalm 119 (118 according to the Septuagint/Vulgate numbering), while also tying in various scenes and events from the life of Moses—and as if that wasn’t elaborate enough, the sections contain sequential allusions to the Ten Commandments. But even if all these subtleties aren’t noticed by the reader, the work remains a compelling meditation on the law, using Old Testament stories and characters to reflect on the abundant life to be found in the sometimes inscrutable but ultimately secure scaffolding of God’s word. In the poem’s conclusion, Moses takes comfort in being found by the Lord, “a lost sheep searching for shelter / On the long leeward slope of your steep windswept law.”

Mountains are important images throughout the collection, from Mount Sinai where the Mosaic law was received to present-day experiences among the majestic Rocky Mountains. There are also recurring scenes of the sprawling Canadian landscape, epic and imposing, eliciting responses of awe, isolation, and regret. Vivid sunrises and sunsets also figure prominently, sometimes bringing crushing, radiant revelations (“The Return”) and sometimes, quiet reflections in simple moments. “Sunrise Over Crow Puddle” is worth quoting in its entirety, to appreciate the evocative imagery and gentle whispers of rhyme.

Sunrise Over Crow Puddle

When dawn reaches rosy fingers

between the criss-crossed tree branches

along the street that meets our house,

she swirls her colours through the water

that’s puddled in our sagged cul-de-sac

like an artist washing paintbrushes.

Here a local crow comes back each day

bringing his breakfast of garbage to eat:

perhaps discarded sandwiches

or a desiccated mouse.

And watching, I almost forget to finish

my coffee. Somehow, I’m always surprised

to discover the subtle range of richness

an unremarkable moment can hold.

In all the houses down our block

the neighbours bustle about their business

as this crow gulps down his carrion

from a chalice of rose-gold.

Travel is also a recurring motif, as Butler gives us depictions of long drives across modern Canadian highways (“Highway 17 Revisited”, “The Lonesome Blues”) and the journeys of the patriarchs in the book of Genesis (“Hospitality”). The travellers within “the long mysterious arc of transit” are sometimes led on by boredom or aimless yearning, sometimes filled with anguish and regret. Often the wanderers are questioning and seeking transcendence, searching for clarity and solidity in the midst of external and internal instability, uttering prayers such as, “Anchor my grand / illusions to your stubborn facts a while.”

The overarching theme of the “living law” is clear in the poems featuring stories and characters from the Pentateuch, but a more subtle line can also be drawn from the Decalogue to the Logos – the ultimate incarnation of the living and active Word of God. Although Christ is not often addressed directly, his name is invoked obliquely in “Mid-Lent,” a deft Golden Shovel on the Paschal Troparion (“Christ is risen from the dead, trampling down death by death…”), and his presence is frequently implied in references to resurrection. There is a thread of tentative but sure hope in the sprouting of new life, as we wait with “expectant ears pressed to a tomb” (“Hymn #735”). The final poem, “The 613” (referring to both the putative number of commandments in the Torah and also the area code for southeastern Ontario), closes on a hopeful note:

And I will grow to thank the living law

which forced my will, and held me here to glimpse

this inward-spreading spring: the heart’s slow thaw.

The collection also has a streak of humour, such as a witty epigram based around a palindrome (“Nepotism also slams it open”) and a sonnet lampooning the pomposity of a self-serious author (“The Writer’s Retreat”). Some poems take on modern social ills (“Against Granville Island,” “The Satellites That Serve Us”), often through heavy use of irony—and to Butler’s credit, he tends to include himself within these ironic critiques. Other highly musical poems riff on lines from William Blake (“Hold to Mercy,” “Rock on rock on Voltaire Rousseau") and old country/folk tunes (“The Vengeance of the Tennessee Waltz,” “The Hammer That Killed John Henry”). While the book is predominantly characterized by weighty themes and spiritual profundity, the inclusion of these more eclectic pieces offer variety that may appeal to some tastes. Butler clearly shows a wide range, and when taken as a whole the collection maintains a cohesive and distinctive quality.

Among the most moving pieces are the deeply personal poems about family, expressing the devotion and loyalty of these bedrock relationships in a way that is honest and relatable. “The Boatwright” is a touching elegy for the poet’s brother, and “Too Much Morningtime” is a tender reflection on his young son’s exuberance. “The Life We Chose” is a beautiful love poem to his wife, written from the trenches of parenthood amid the literal constraint of sleeping arrangements with little kids, which also ties back into the collection’s central theme of the freedom and possibility to be found in acknowledging and accepting limits within the “long cascade of choices” that necessarily defines a life—a sentiment that will resonate with any parent, as well as any poet who chooses to work in form.

We’ve made our choices. What we chose

is this. We’ll see what this can be

with time and love. Tomorrow is

our ten-year anniversary.

Life moves so fast, but it’s immense.

It’s rolled out like a long cascade

of choices, sometimes packed so dense

we’re not quite certain which we’ve made.

But here it’s brought us—to our sons,

and to this hollow, dragging night.

Some choices you don’t make just once—

you choose and then you hold on tight.

With his debut, Butler joins the robust tradition of poets demonstrating that there is still much beauty and meaning to be mined in contemporary manifestations of metrical, rhymed verse. These poems are memorable and speak to universal truths, offering a welcome entry to readers who are less immersed in the poetry world and may be put off by more prosaic, ephemeral, or esoteric varieties of poetry. Butler’s work is both accessible and rich, and in The Living Law, he probes the depths with poems that sing.

Steven Searcy is the author of Below the Brightness (Solum Press, 2024). His poems have appeared in Southern Poetry Review, Commonweal, The Windhover, UCity Review, Autumn Sky Poetry Daily, and elsewhere. He lives with his wife and four sons in Atlanta, Georgia.

Jesse Keith Butler is an Ottawa-based poet who recently won third place in the Kierkegaard Poetry Competition. You can find his poems in a variety of journals, including Arc Poetry, Dappled Things, Blue Unicorn, On Spec, and The Brazen Head. His first book, The Living Law (Darkly Bright Press, 2024), is available wherever books are sold. Learn more at www.jessekeithbutler.ca.

So wonderful to see a review of poetry so well-informed by obvious knowledge of the form! My poetry professor would be pleased. https://geekorthodox.substack.com/p/mentors-direct-and-indirect