Good Want by Domenica Martinello (Coach House Books, 2024)

Reviewed by Katie Schmidt

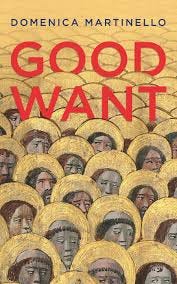

The opening of Montreal poet Domenica Martinello’s second poetry collection, Good Want, feels like we’re about to witness a knife fight with morality. Before the poetry begins, the collection throws down the gauntlet to sanctity. The cover depicts a crowd of saints in the style of icons, but whose golden halos block each other’s views. These figures are given no spatial reverence but are crowded together like a sea of concert goers shifting from foot to foot, giving each other side eye or looking off into the distance. None are offering us a tonsured intercession to God, but are looking a little bored, a little tired.

This book will not be concerned with genuflecting to the divine, this cover promises; a promise reinforced by the opening epigraph from the American poet and essayist, Mary Ruefle, “I have often thought god needs prayers to remind himself he is important, and still matters. Without our interceding glances, what would he be but a shrunken head on the end of a thread in a museum of ideas?,” and the epigraph to the first section from the New Zealand poet Hera Lindsay Bird “You do not have to be good./Being good isn’t even the point anymore.”

It would be easy to think from this introduction that Martinello is going to offer a treatise on why virtue and God are outdated concepts; yet instead of being a persuasive offense against morality, the work reads far more interestingly as a defense of the infinite desirability of the physical world.

In 2010, Philip Pullman, the renowned young adult fantasy writer, published a book called The Good Man Jesus and the Scoundrel Christ, which aimed to debunk the gospel stories through a humanist retelling with all the arch smugness of an older brother telling you Santa isn’t real and you were stupid to believe he was. It was the most boring book I’ve ever read.

Martinello’s collection couldn’t be further from taking this angle; rather, it presents a bracingly honest struggle against the restraints on desire, not merely sexual desire, but a desire for the particularity of being human. The poems range from stories of growing up, of economic want, of the shadow of academia and religion, to explorations of the psyche, guilt, pain, and a strange homage to Mary Oliver.

Her work is confrontational, challenging the history of interpreting desire as something to be suppressed, something innately sinful, but her project is not one of rejection. In the opening poem, “I Pray to be Useful,” the speaker walks up the stairs of an oratory–perhaps like the formidable St. Joseph’s Oratory of Mount Royal in Quebec–and says:

Each moment is a new bead to balance on, and each bead felt wrongly sumptuous as I prayed to want less.

The poetry wrestles with this problem of the “wrongly sumptuous” world. How can we want less, and how can it be wrong to want less, when the world is made with such profound, delicious detail? The poem ends with the impossibility of curtailing this hunger for the world: “Like my hands,/ my hunger never/ hardened over.”

What the poet defines as want and its proper object is not a delineation of hierarchies, or proper modes of desiring, but an inclusive, expanding, borderless hunger, like the lusty inclusivity of Walt Whitman’s Song of Myself. In the prose poem “Butter Receptacle,” Martinello enumerates,

I like the admin work, I like zip-locking, the ad libbing, the serenades at nap time, killing a game of charades, feeding two birds with one scone, letting the cats keep their skin, finding a way, breaking capsules on my face, disappearing veins, the oil pull, the masking, the flushing, the versatility of mould, its flirty fuzz, black or white, wet or fluffy, spores, s’mores by the radiator,...

The poem is an unlikely abundance: a sonic romp, jamming together unlike ideas, which depict the quotidian as a sensuous feast, mould bumping into s’mores. The speaker desires the intense particularity of everything, the minute detail of the ordinary, down to the playful mundanity of idioms. The power of the poetic voice in this collection lovingly and unflinchingly details the physical world, standing in defense of wanting what the poet calls in the titular poem, “Good Want,” “generic.” Martinello’s incredible ability to elevate what is “generic” to the level of aesthetic delight gives the poetry its most persuasive quality.

Martinello’s poetry often achieves its richness through surprising comparisons to and about the body, food, and the earth. For example, in the first poem of “Vague Feast or, six sestets one silent,” these images intermingle:

there are many things I want to do with a paring knife: unburden the world of its softness, disrobed in one endless uncoiling peel. pears are winter fruits, I am too, whatever you think that means.

The collection is replete with these images and they serve both as reminders of the fleshiness of the body–that we are not just big brains or incorruptable souls wearing an unfortunate but irrelevant coat–as well as elevating the physical world to the level of the artistically significant in a way that doesn’t abstract it but further emphasizes its physicality. “Power Ballad (Hymn)” addresses this use of language directly:

My body is a metaphor of the body as a landscape cluttered with loaves and fish in baskets. I’ll never be conceptual. I am one with the masses.

The body is a metaphor of the body as a metaphor. The physical is always given priority as the purveyor of meaning. The poems often dwell on the body, celebrating its unromantic reality:

I lock fingers with myself, preteen. I offer up the underwire. I

bounce and supple, drag and drop the pretense, steal. My fanny

pack is plump, I smell all pungent and powdery.

("Circling Back")As readers, we are never allowed to escape into the comfort of the abstract but are always smashed back into the earth, as though the poet is holding our faces to the dirt, to the flowers, to a sweaty armpit and telling us to breathe deeply. One of the most striking parts of Martinello’s work is how genuinely funny it is. After my daily online wash of blandly relatable content, this collection kept surprising me with its clever bawdiness and cheeky metaphors.

Then again why does everything need to say something The hot doctoral candidate in my head says, Why not in that perfect existential tone He trilingual, cunnilingual, knows how to cook in that accomplished, undomestic way ("In Bad Dream")

Carried through these poems, though, is a current of past and present episodes of violence, shame, and guilt. In light of this suffering, the poems wrestle with the usefulness of goodness, prayer, and even writing poetry. “Good is what happens/ when you stretch God too far.” the speaker says in “Good Want,” and in “Asking for it,” says,

Poetry often feels to me like clicking the beads of a rosary. It’s not hurting anybody, I guess, but that doesn’t make it virtuous.

The speaker is ambivalent about the usefulness of goodness, morality, and poetry in the light of experienced suffering, of shame, guilt, and frustration, and she desires freedom from these constraints: “I am the caretaker of good and bad/and I loosen their reins.” (Good Want). Yet, this ambivalence manifests not in a persuasive rejection of morality, but as the struggle of reaching towards an antidote to suffering. In “Little Light,” a poem about the speaker’s expectations for grandeur in the world, she says,

I thought there'd be a film, some protective coating. Yet I stand in my life, a raw sunburned nerve

The surprise and delight of the language of Martinello’s collection seems to reach for being this “protective coating,” the resplendent depictions of the unlovely physical world help to make meaning out of the mundanity and painfulness that comes along as part of existence. As the speaker says in “All the Trimmings,” “waste not your wanting.” The poetry seems to be turning desire into an enchantment of the world.

Desire is not only erotic lust or greed but love for being alive, being a human, a body, flesh in a fleshy world. The speaker is peering at everything, the garbage, the rashes, the dirt, and saying this too is lovable. It is no wonder that the speaker finds a poetic companion in Mary Oliver, who explored the themes of the sacredness of the natural world.

The collection both praises and struggles against Oliver, especially the themes of her famous poem “Wild Geese.” This poem depicts a loving, accepting relationship between the natural world and the creatures in it, and the desires of humans are peacefully accepted: “You only have to let the soft animal of your body love what it loves.” And yet, Oliver’s work seems to find peace too easily for Martinello, lacking the darker material realism of her own work.

In fact, Martinello’s descriptions reminded me more of Gerard Manley Hopkins, whose attention to the bright and gritty particularity of the world uncovers hidden richness, like in “God’s Grandeur”:

The world is charged with the grandeur of God.

It will flame out, like shining from shook foil;

It gathers to a greatness, like the ooze of oil

Crushed. Why do men then now not reck his rod?

Generations have trod, have trod, have trod;

And all is seared with trade; bleared, smeared with toil;

And wears man's smudge and shares man's smell: the soil

Is bare now, nor can foot feel, being shod. Reading Martinello’s collection, I cannot help feeling her rich poetic vision as having a devotional quality, perhaps not towards God but towards the intimate detail of the created world. The collection takes us far away from the quiet, lifeless frames of saints and into the noise and wreck of the world they once inhabited. Where to desire is not to sin, but to be drawn deeper into the world.

Some desire is for the stuff of beauty, some for real need of food and sleep, some for the ordinary, for scraps, for refuse. “Waste not your wanting.” In the world of good want, it is impossible to escape want and impossible to see it as a sin. It is the tether that holds us to the material world, and the material world is merged with the psychological, the spiritual, and the literary. There is no separating them, there is no escaping from the body into the abstract. We are jolted through the unlovely world without the respite of romanticization or idealization. And yet this world is made richly tangible, refuse is made delicious, lovable, desirable. We are at once having our eyes pried open to the stuff of the world, and that world being offered to us as a gift like happily steaming shit on a silver platter.

Katie Schmidt is a writer, editor, and artist from Ontario. She holds a Master of Arts and Religion from Yale University and a Bachelor of Arts in Literature and Writing & Rhetoric from the University of Toronto. She is co-poetry editor at Traces Journal.

Domenica Martinello holds an MFA in poetry from the Iowa Writers' Workshop, where she was the recipient of the Deena Davidson Friedman Prize for Poetry. She currently lives in Montreal.