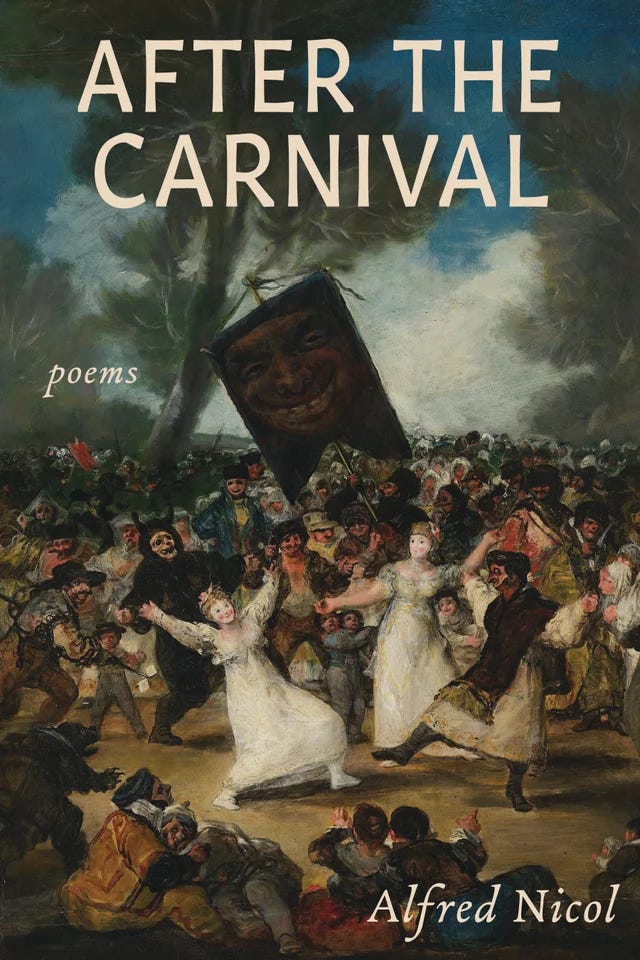

After the Carnival, Poems by Alfred Nicol (Wiseblood Books, 2025)

Reviewed by Celia Jordan

For many, the idea and practice of carnival are foreign concepts. There are, of course, some exceptions. Mardi Gras celebrations continue to be a favourite holiday in places like New Orleans, for example. But by and large, secular societies have dispensed with the hurly-burly festivals – those nights of role-reversals and chaos that have served their societal purpose in both the East and West through much of history.

Scholars have offered explanations of their disappearance. A central theory, articulated by Charles Taylor, among others, is that our society cannot admit chaos as an active principle. We are deeply unsettled by it, and so we pretend it does not exist. Our lawns are manicured, our slaughterhouses out of sight, our vagaries sanitized and psychologized.

Alfred Nicol’s latest volume of poetry, After the Carnival, forbids us the luxury of ignoring the chaos we have cast to the margins. The collection’s premise is that chaos lurks in everything – the banal is tinged with the grotesque; the quotidian is anything but casual. Needless to say, these poems are not “sweet-smelling flowers” held out for our delight; the overall tone of the work, at least that carried by its subject matter, is heavy.

The collection’s opening poem warns us that the path we are on doesn’t “tak[e] [us] very far. / It only brings [us] back to where [we] are.” Well, ‘where we are’ in the pages that follow is more often than not a frightening place: the mind of a troubled murderer, the home of a child-killer, the thoughts of the lonely and isolated.

And yet, the darkness that either colours or flutters in the corner of every poem does not feel oppressive. This, I think, we can attribute largely to Nicol’s effective use of form. Readers already familiar with his work will find in this collection all the formal artistry and playfulness they have come to expect from him. His language and lines are often exquisitely crafted. But here, the reliable structure and lightheartedness of his verse is working overtime: the juxtaposition of the Puckish rhymes and rhythms with the unsettling subject matter is strangely provoking.

In “Nuclear Option,” for example, the speaker asks us to consider writing the names of everyone we’ve ever known on a paper, which we are then to consign to fire. We will see, on that paper,

mixing with men of poison minds the man of conscience in his cell. Oblivion accepts all kinds. Farewell. Farewell. Farewell.

The terror of oblivion, the fear that everything will go up in smoke and no auguries will be read from the ashes, is ostentatiously absent from the tempo of these lines. Form and content are at odds in a way that is both unsettling and, as we continue to read, reassuring.

It is difficult to name exactly what about the tone of many of Nicol’s speakers keeps us from sinking into despair. After all, it can sometimes feel that we are on a merry-go-round in a fairground of unease. It starts gradually in the first of the book’s six sections, All the World There Is. Here, only moments catch us off guard. In “A Notable Catch in a Tourist Town,” the tuna hauled in by a fishing boat draws the attention of bored seaside tourists, who gather round for the excitement of “food outside of fridges,” which “breathless, … still can bleed.” The poem ends with a young boy who “cuts through the crowd and thrills / to catch a glimpse inside the gaping gills.”

Through his penetratingly honest gaze, Nicol continues to reveal to us what lurks inside the “gaping gills” of ordinary life. In “Stay At Home Advisory” – a quarantine poem – the speaker asks us to pity the perpetual recluses, those who have always shunned the society and companionship we so desperately missed during the pandemic. The poem ends,

But those you pity may well ask, estranged, Was it not ever thus? Who goes outside without a mask? So what is quarantine to us?

Who goes outside without a mask? The carnival is not contained, nor an extraordinary measure. We wear our masks of normalcy to hide the carnivalesque behind. Just as in many traditional carnivals, where revellers would wear animal masks, it is often the animals in Nicol’s poems that alert us to the reality that we – wilfully or otherwise – miss.

In “Blizzard,” when his dog drags him outside during a storm, the speaker notices the austere beauty of the night. He muses, “all the world there is / under the nose of dogs who drag their fools / from here to there.”

The speaker in “Blizzard” labels himself the fool; this is a uniquely fitting title for many of the speakers throughout the volume, and it is the spirit of the jester that enables both the frightening confrontation of our hastily hidden hypocrisies and the ability to handle it without self-pity or despair. It is the jester’s spirit that sings, “Farewell. Farewell. Farewell.” It is the jester’s teasing role-playing, pretending to take on the view of the masses to expose their lunacy, that reigns in the voice of “The Man in The Middle.” Of the figure held up by the crowd as a hero, only to be turned upon when he fails to tow the line, the speaker enthusiastically incants,

We're not apt to thank him. We'll spank him and yank him and toss him in pieces on top of the heap.

Even in the poems that are not in this ironic, half-mocking mode, there is the jester’s refusal to commit to a side: truth demands that neither despondency nor triumph be given too much ground. It is hard to gaze honestly at things and not sink into silence. At times, it is a silence that brushes despair – an inability to find comfort because the horror or senselessness or utter banality of the thing makes all action meaningless. At other times, the silence is revering, an homage we pay to a beauty or goodness that absolutely surpasses words. The value of Nicol’s poetry is the persistent striving towards silence that is neither of these things, while acknowledging both.

We do not sense in Nicol’s verse a spirit that takes refuge in the little miracles of beauty that surround us – the flower opening towards the sun, the intricacy of the bee’s activity, etc. This is not a volume that marginalizes despair by dwelling on the quiet abundance our distracted eyes miss. Rather, it is everywhere, rushing into his lines, threatening to burst the project at its seams.

“The Surface,” whose epigraph is a quotation from Sartre, begins, “There is an emptiness in everything, / like the shade cradled in the crescent moon.” Nicol wields his imagery masterfully here and throughout the poem to evoke the sinking hopelessness that comes when the abyss starts to show itself in everything:

another shade that walks the streets alone, past windows—yes, the windows too are blank, where people dwell inside their separate lives, huddling there like money in the bank— to where the river sheathes its glinting knives.

We could note many things: the conversational tone, the allusions to Eliot’s “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” the effective use of rhyme, and the lack of self-indulgence when confronting the void. The poem is unrelenting, but it does not yield itself to the “néant” altogether. The final lines are ambiguous: “The tides have seized; the stillness is unreal. / The surface poses as a sheet of steel.” It is not an absolute assertion – “poses” plays an obfuscating role. Is the water really, devastatingly a sheet of steel? Or is it merely appearing so to this speaker at this time?

The opening image of this poem is echoed in “His Eyes Rest on Julia, Sleeping.” Instead of the crescent moon that cradles shade, here it is “the hollowed stone that cups the rain.” Unconscious of itself, this stone brings comfort and coolness to the speaker, who proceeds to list other phenomena whose beauty or enjoyment is not for its own sake but for ours. The poem ends, “So love, that turned this world and gave it shape, / has need that I should keep watch through the night.” This, too, is a close that thwarts easy interpretation – “need” is a heavy, unromantic word that might be read as vainglorious: love does not exist unless I notice it. The poem’s title also renders the final lines ironic: a man gazing at a woman asleep is now almost always freighted with some uncomfortable undertones. And yet, through this, there is a sincerity to the sentiment, and an honest reminder that we pay attention to the beauty of this world; a recognition that it is not fully itself unless its succour is accepted.

Nicol’s ease with ambiguity carries through right to the end of the volume. The last poem, “Gibbous Moon,” nearly quivers with the anxiety of insufficiency, as it articulates the human experience of receiving half-comforts, barely enough to survive the corrosive effects of time and pain on the soul. The speaker catalogues images (in a way powerfully reminiscent of Herbert’s “Prayer I”) for the “unheralded” gibbous moon that appears in the sky “too late, / if not too soon”: a lopped mushroom cap, unfinished handwork set aside, a moth-eaten lace doily, and - my favourite - “age-spotted face obscurely seen / peering through a storm door screen.” The catalogue ends with this final image:

thin wafer vagrant souls are fed, wholly insufficient bread we bless and break, and multiply.

There is no absolute turn of confidence towards God or the Eucharist and its redeeming power. There is not, even, the assertion that God multiplies our efforts. We are the ones multiplying. The pause between “bless and break” and “multiply” is important. We are blessing and breaking the “wholly insufficient bread,” and then comes the multiplication. What are we multiplying? Ourselves, according to the commandment; our efforts; our works of art? In any case, everything is tainted by the inadequacy of the bread, and yet we continue. The very action of multiplying speaks of acceptance and of hope.

After the song and dance, what is left? An insufficiency we must pick up. Nicol invites us to reckon with the chaos we would rather avoid - and to act anyway. These poems are not ones to pick up when looking for the kind of galvanizing inspiration towards noble deeds and moral struggle that you might find in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings, for example. As his speaker says,

We don't invite the epic muse to visit. Heroic figures make a lot of noise. Who needs another lliad? Not me. That sort of thing plays better on TV.

No, this is a work to pick up and draw great comfort from when the leering horror of life peers at you through the chinks in your routine. When they will not stop staring, and the foundation is threatening to crumble beneath you. Nicol, with irony and the lightest touch, does not divert you from the ugliness - he delves right in, he doubles down. But neither does he drop the obligation to be sustained and to multiply. After the carnival, bleary-eyed and head aching, we stumble to greet the sun.

Celia Jordan earned her Master's degree in English Literature from McGill University, where she wrote her thesis on figurations of sin in the poetry of George Herbert. She now lives in Montreal, and continues to work on her own poetry. When she's not writing, she works in art acquisition and as an administrative assistant for an Ontarian non-profit that ministers at the intersection of theology, ecology, and the arts. Her current idea of a hobby is (very slowly) painting a wardrobe in the Tyrolean style.

Alfred Nicol, who worked in the printing industry for over twenty years after graduating from Dartmouth College, published his first book of poems, Winter Light, in 2004. His other publications include Animal Psalms, Elegy for Everyone and Brief Accident of Light, a collaboration with Rhina Espaillat. Nicol’s translation of One Hundred Visions of War by Julien Vocance, has been called “an essential addition to the history of modernist poetry.” His poems have appeared in Poetry, The New England Review, Dark Horse, Commonweal, The Formalist, The Hopkins Review, and in many anthologies including The Best American Poetry 2018 and Contemporary Catholic Poetry. His translation of the lyrics to "Győzelemről énekeljen," were used for the official anthem of the 52nd International Eucharistic Congress, convened in 2021 by Pope Francis in Budapest. As part of the music-and-poetry ensemble The Diminished Prophets, Nicol has performed melopoeia for over twenty years with Espaillat and classical/flamenco guitarist John Tavano. In recent years, the Newburyport Chamber Music Festival has commissioned several works of poetry for its annual event. Nicol lives in Massachusetts with his wife, the artist Gina DiGiovanni.