Augustine (354–430 CE) taught that we are to order our loves correctly. In simplest terms, we are to love only God, to desire only him, to enjoy only him. Relative to the enjoyment of God, everything else is only to be used. To enjoy something other than God is to make an idol of it. It is to set that thing up as a rival good to God.

There is a simplicity to this formulation that is breathtaking and invigorating. It’s breathtaking in the demand it makes: Put all your eggs in one basket. Love God only.

The formulation is invigorating because it simplifies life’s task and makes it seem doable, if only in its simplicity. At least one won’t get tripped up reading the instructions.

It is useful to recall this distinction between enjoyment and use often. I offer the title of this column as a mnemonic aid.

As for its content, this column affords me the opportunity to collect examples of a commonplace cultural trope: love-and-reason-in-tension. Eventually, I’ll consider contexts for the appeal of the construct. For now, though, I want simply to gather examples to clarify, not least for myself, what I have in mind.

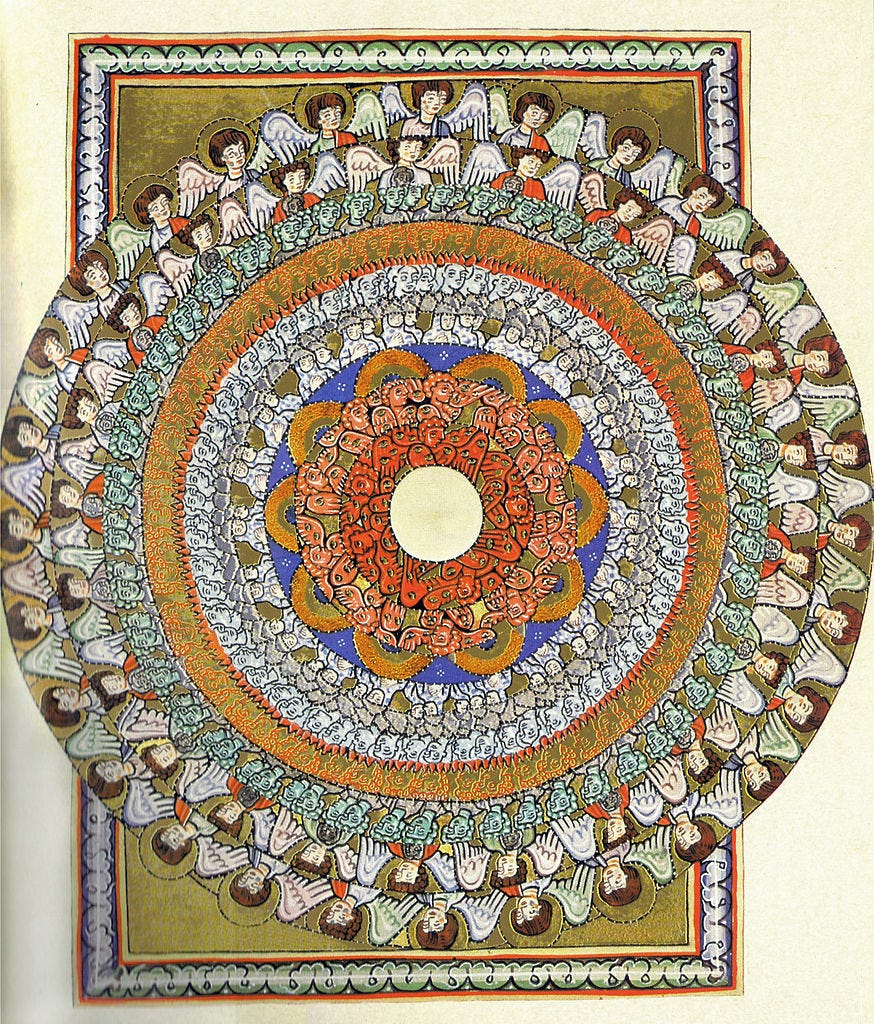

These examples will include the historical and philosophical, such as Plato’s image in the Phaedrus of Reason as a charioteer driving two horses, one of which is Passion, and the Stoics’ radical redescription of the soul as entirely rational, the passions being relegated to the effect of misconstrued appearances. They will range from the sublime to the ridiculous. Some will be drawn from contemporary culture. I intend to meditate, for instance, on the centred episode “The Compass” from Lost (S4.E5), and to comment on the climactic one in Season 1 of Mad Men, in which Don pitches the “carousel” to Kodak.

“The basic feature of love-and-reason-in-tension is paradox.”

The basic feature of love-and-reason-in-tension is paradox. It’s there in the phrase “the order of love.” Love carries with it the connotation of consuming desire, utter devotion, taking the plunge into the unknown, allowing your reality to be ordered by your commitment to the object of your love, your beloved. It carries with it the assumption of obedience and therefore of having submitted your will to that of another. This is especially so with reference to the beloved or to love for God. There are other loves – brotherly love, friendship, the love of country; these partly take their meaning from the intensity associated with the love of God or of the beloved or are secondary to them, at least in the context of the trope of love-and-reason.

Yet this love is ordered. It invokes the idea of order and, with it, inalienable rationality. If one is supposed to enjoy only God, then one must be vigilant and keep an eye on one’s heart. One must discern the signs to ensure that some other object of devotion isn’t stealing one’s attention away from what is to be its real object. Often, the ordering of love is a matter of ranking many different things in one’s life so that they collectively reinforce the sense of being ordered to the ultimate love of God. This process of discernment involves interpretation, including recollection, reflection, and articulation (to self, perhaps to others, and, in an interior dialogue, to God). This process is rational and intellectual, at least in part. The injunction to love only God carries with it the expectation of cerebral work.

Enjoying only God (and obeying his order out of love) involves reason in another way, too. There is a dimension of this experience that involves the overwhelming sense of having heard, of having understood, of having had something revealed to oneself: Is this a task that God has set before me? What is it that I am required to do? Have I heard the voice of God rightly? Am I reading this correctly? Is this being said to me? Is this for me?

Sometimes we think of it as conviction, something of an order that one is best advised not to try to explain or dissect. Paradoxically, part of the sense of a required obedience or action is the call to “test the spirits,” to take the counsel of friends, to reflect and act wisely. So this part of responding to love, too, involves the mind, recollection, articulation, interpretation, and discernment.

The processes of affirming the supremacy of love can involve others in radical ways. On the one hand, these processes might seem to be necessarily introspective and largely private. Yet this need not be the case. They can (and normally will) involve sources outside oneself, like Tradition (or Church Teaching) and Scripture. Appealing to authorities involves decisions that have already been made somewhere along the line (and continually reinforced) about what constitutes a source of authority. These decisions involved the mind, though they too always involved reason operating with love in an ever-deepening hermeneutical circle. One responds to authorities with an attitude of the heart; at the same time, one is confident of the coherence of the source of authority. In part, one anticipates an understanding yet to be revealed.

“The processes of affirming the supremacy of love can involve others in radical ways.”

The order of love means many things. In its root Augustinian sense, it means setting the love of God above all other loves. The phrase also involves a meaningful paradox and a call to respond to God with all of one’s being. It is a matter of responding, because antecedent to all of this activity is the soul’s passivity before a God and a Love hungrier for me and nearer to me than I am to myself.

Norm Klassen (dphil oxon) is Professor of English at St Jerome’s University in Waterloo, Canada, with a background in theology (B.Th.), history (B.A. Hons), and literature (B.A. Hons). He has taught literature for over thirty years and is the author of two books on Chaucer, one on literary theory, and co-author of another on higher education. The two paradoxes that seem to have preoccupied him in his work in the vineyard have been the relationship between Christianity and culture and that between love and reason.

Thanks Norm, thoughtful as always! I am intrigued by the way you are bringing authority into the conversation. Authority is such a difficult thing for us moderns to grasp, and putting it in the context of love and reason seems bang on.

Andrew K