All Creatures Praise: A Conversation with Josh Tiessen

A Conversation between Josh Tiessen & Maya Venters

Josh Tiessen is an international award-winning contemporary artist based near Toronto, Ontario. Tiessen is best known for his hyper-surreal shaped oil paintings, which take up to 1700 hours to complete, and reflect the interaction between the natural world and human-made structures. Drawing upon his studies in theology and environmentalism, Tiessen holds a B.R.E. in Arts, Biblical Studies, and Philosophy, and an M.A. in Art History from the University of Toronto.

Tiessen’s latest solo exhibition Vanitas and Viriditas is an exploration of two divergent perspectives on wisdom, and how we might flourish in a modern society filled with facts but mired in confusion.

He was interviewed by Maya Venters via Zoom after the opening night of Vanitas and Viriditas in September 2024.

Maya Venters for Traces: To situate your artwork within the larger traditions of Canadian painting, can you talk about your apprenticeship under Robert Bateman and how he influenced your work?

Josh Tiessen: Robert Bateman’s artwork was among my first exposures to Canadian art and my early paintings definitely reflect his naturalistic wildlife scenes. When I was fourteen, I had my first solo exhibition at the Art Gallery of Burlington. Bateman was from the area and was a supporter of the gallery, so someone suggested I write him a letter. So I did and he wrote back inviting me to a master artist mentorship in British Columbia. There, he critiqued my painting "Nesting Trumpeter Swan," which I was very nervous about because most of the artists there were double to triple my age.

But I didn’t want to be pigeonholed as strictly a wildlife artist early on. I was interested in old weathered architecture, and I wanted to experiment with various abstract styles.

Eventually, I became interested in incorporating theological themes, animals, abandoned ruins, and more apocalyptic scenes. I think I gravitated to not just Bateman's idyllic landscapes, which characterize his early work in the seventies and eighties, but I really liked his latter work, like in the early two-thousands and nineties, where he started showing the encroachment of human civilizations on animal habitats. I explore more of that world in my paintings.

Traces: This sense of the natural world encroaching on human structures is a thread throughout Canadian painting. But any destruction or hopelessness is often depicted alongside elements of life flourishing. Your work, for example, in Nirvana 5G, uses the technocentric and apocalyptic to probe at truth and beauty. How do you use elements of decay and artificiality to gesture toward the true, beautiful, and good?

JT: Whenever my paintings depict destruction or lamentation, I try to make them beautiful through the colour palette and the handling of light and shadow. You cannot have ugliness for the sake of ugliness.

My "Streams in the Wasteland" series is where I began thinking about natural reclamation, which is now a common thread throughout my work. The Book of Isaiah was the unusual reference point for that series because there are these prophetic visions that Isaiah poetically writes about of the destruction of Babylon strongholds. There are hyenas that would inhabit the mansions, and owls and jackals taking up these places of power.

So in some ways, it’s a reminder of the frailty of human civilization. I think that goes to the root of a lot of our ecological issues today: this notion that humankind is the controller of the environment and the sole center of value, an anthropocentric approach to the world. And so I think that while some of these paintings can be challenging for viewers to see, hopefully, they provoke a deeper thought.

Traces: You seem to have a very global perspective of the arts and the landscape. Your exhibition invokes the question of what it means to be a citizen of the world. How do you see yourself as a globally-oriented artist and as a citizen of the world, but also as someone who is rooted in a particular place?

JT: I’m affected by being a third-culture kid. I lived in Russia for the first six years of my life and travelled with my family for most of my childhood and for some of my adolescent years. I want to be globally minded. But in my latest painting series, Vanitas + Viriditas, I think more about place, and particularly, being content knowing the place where I live.

One of the challenges with environmentalism is that we can be so aware of large-scale effects on the planet that we forget about the local concerns. I’m still learning to be rooted in where I am and not take it for granted. As I’ve grown, I've realized how unique my area of southwestern Ontario is, where I have wetlands, waterfalls, the Great Lakes, the escarpment, and the Bruce Trail right by my studio.

Traces: At times, your paintings act as modes of preserving creation. In Agnus Dei, for example, extinct species are re-membered on headstones in the background. This painting and your use of animals call to mind the phrase “creation care,” which comes up throughout your book Vanitas + Viriditas. What does this phrase specifically mean to you?

JT: The word "creation" is important because it ties the natural world to a creator. I don’t like the term “nature.” I find it demystifies and secularizes creation, making it something outside of human experience. I think similarly with “environment;” it’s quite nebulous.

Some scholars use “earth-keeping.” I like “creation care” because it doesn’t specifically center the conversation on politics, which, unfortunately, turns people off from environmentalism. Some people think that environmentalists are just covert Marxist leftists. I think it could be a bit more disarming to people of faith who hopefully see stewardship as being something grounded within Genesis 1:26-28 about how the Garden of Eden was meant to be stewarded: we are to have dominion. That word dominion, unfortunately, can get misinterpreted, but it’s the same word attributed to Christ in the messianic psalms about servant leadership.

I think creation care for me was something I came across a little later. I'd always been a great lover of the natural world, and being with Robert Bateman inspired me to think about it artistically. But then when I went to Bible college I came across “eco-theology” and discovered that there are Christian thinkers and theologians who have argued for creation care as part of the Christian calling.

Oftentimes, we think that the earth is something humans own, but Psalm 24 talks about how the earth and everything in it is the Lord's. If we think of God as a master artist, whom we love, we should also love the things he's created. I think this whole world, the cosmos, is a masterpiece, and humans are the crowning jewel of that masterpiece, but all of creation is imbued with wonder and glory.

Traces: Thinking about God as the master artist, how do you see yourself as a co-creator or participant in the act of creation?

JT: J.R.R. Tolkien uses the term "sub-creator." That’s very humbling because we don’t create ex nihilo, out of nothing. We start with raw materials, and sometimes I feel that artists can be too disconnected from their materials. For instance, I’ve tried to develop a non-toxic studio where I mix my paints from raw pigments. I don’t use solvents—just walnut oil and natural mediums.

We read in Genesis about how the descendants of Cain made musical instruments and tools from forging raw materials. That’s also reflected in the creation of the tabernacle and temple. We are always working with the earth.

I try to be mindful of where my materials come from. For example, I paint on Baltic birch panels, which originate from Russia, from the Baltics. Being originally from Russia myself, it’s a neat connection for me to think about. I don’t think artistic creation needs to be at odds with creation care, with a relationship to the natural world. Artists may be some of the people most connected to the natural world. The cultivation of natural resources—and I don’t love that term—is part of the Christian mandate as well.

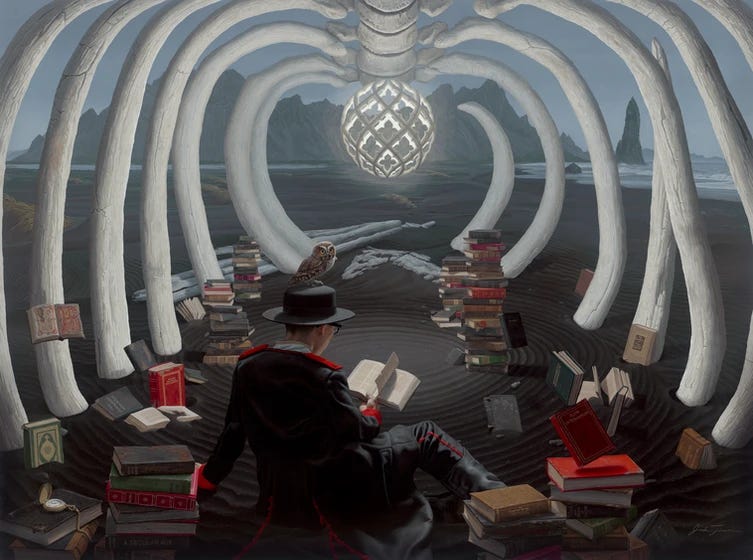

Traces: It’s clear that your artwork draws heavily from various theological and philosophical texts. Your exhibition emphasized the influence of Jewish wisdom literature on the current collection, and Aaron Rosen has called you an "artist bibliophile." What do you think of that category of artist?

JT: That term took me a little by surprise, but it is quite fitting. I’ve always been interdisciplinary in my work, pulling from various fields. Art history is very important to my work—history in general.

The art world can be an echo chamber, a self-referential space where we don’t always draw from other disciplines. I think the academy can be siloed in that regard. Studying art history at the University of Toronto reminded me of how art history intersects so many other disciplines, like theology and philosophy.

I gravitate to iconographic methodologies in interpreting art. I’m interested in symbols and narratives within painting, and that became an important aspect of my work early on. My paintings reflect ideas I’m pondering and serve as a visual diary of sorts. Each work takes years to develop, as I sketch, think, and read.

But I don’t just see painting as illustrating philosophies. I think painting is its own epistemology, its own source of knowledge. It’s visual theology, and that can be missed. What we can learn about life or faith through painting is important, valid, and distinct from other ways of knowing.

Traces: Music is another mode of knowing, in this sense. Your brother, Zac Tiessen, composed an original score to accompany the Vanitas and Viriditas exhibition. In addition to the textual influences, are there liturgical or musical influences that have also gone into this series?

JT: Yes. When putting together this series, I knew I would have the Vanitas paintings with Qohelet, inspired by Ecclesiastes, and the Viriditas paintings with Sophia. I put together two separate playlists of music for each set. For the Sophia paintings, Max Richter’s On the Nature of Daylight, a contemporary classical music piece, was an important reference point. For Qohelet, I listened to Father John Misty, John Mark McMillan, and Arcade Fire’s Everything Now, which has protest songs against technology and consumerism.

Traces: There are times when the Vanitas and Viriditas paintings feel like two distinct aesthetic projects. But in the painting In This Birch Grove, these two projects come together. The character of Sophia is met by the aesthetic world of Qohelet.

I have a personal interest in what I call a "tradition of mauve" in Canadian art history (which is also present in Russian art), where winter scenes are held together by a mauve-gray palette. The Vanitas paintings use a similar palette, working as a bridge between despair and hope the way we see in Canadian art. How do the resonances of your Canadian and Russian heritage, threads of hope and despair, and the larger themes of Vanitas and Viriditas come together in this painting?

JT: The Qohelet paintings are more monochromatic, achromatic, cool and gray. This was the first painting series where I selected a very limited colour palette for the respective paintings. In This Birch Grove draws more on those cool purples, mauves, and grays. Yet Sophia is present in it, and her dress reflects the colours in the springtime palette of greens and warm sienna tones.

I hadn’t painted anything reflecting my Russian heritage before, so this was a first for me. Birch trees are Russia’s national tree, often seen as having magical powers and planted around Orthodox churches. Winter scenes are common in Russian Impressionism, a painting tradition that is very melancholy, as you could expect, like the realist painters of the 1800s— Ilya Repin and Ivan Kramskoy, for example.

But there’s also Nicholas Roerich, whose work is similar to the Group of Seven and Lauren Harris’s stylized forms. You get the beauty of the landscape but also its desolation. The Group of Seven was very influential to me as well.

I approach colour like an Impressionist painter. When putting together a colour setting, I start with a limited palette to set the emotional tone and mood before diving into hyper-detail.

Traces: In This Birch Grove is also a painting of encounter. Can you speak to the meeting we see between Sophia and the bear?

JT: Initially, I wanted to reflect more on the Russian Orthodox churches in ruins and the grave markers, thinking about the Soviet era and the millions martyred, whether political dissidents or Christians or priests rounded up in the Gulag. But then, with Russia’s war in Ukraine, this painting was going to be seen in a new light because the bear has often been a symbol for Russia—the bear from the north—or in Russian fairy tales as "Misha the Bear," a beloved character.

In this painting, you see Sophia encountering this wild bear. Her gesture of peace and welcome reflects that she is Lady Wisdom; Proverbs says, “a gentle answer turns away wrath.” Unfortunately, in war and politics, we often pick sides in conflicts. With the current situation, for instance, we demonize all Russians. My parents and I have colleagues in both Russia and Ukraine, and we pray for peace.

Interestingly, a Russian man in his twenties saw this painting on Instagram and told me it encapsulated his experience of what he was going through—showing both the beauty of Russian heritage and its destruction. The title of the piece comes from a poem by Nikolai Zabolotsky called In This Birch Grove, which expresses anguish and sorrow but also hope for a brighter day.

Traces: Seeing all these paintings together at your exhibition, there is an arc-like quality to your work. This goes back to the global perspective we talked about. In many pieces, it feels like the animals of the world are coming together, especially around the altar in Agnus Dei. How do you see your paintings as spaces between a destroyed world and a new one to come?

JT: I’ve been influenced by what’s called eco-dystopian worlds or cli-fi literature. Margaret Atwood’s MaddAddam Trilogy has been an influence, as she’s an environmentally aware Canadian author. Her book The Year of the Flood recounts the story of the God’s Gardeners, with a lot of theological and biblical references.

Unfortunately, a lot of apocalyptic films fall short by focusing on destruction and decline for entertainment. With the “imminent frame,” as Canadian philosopher Charles Taylor calls it, there’s no transcendence or hope beyond human effort. I think hope does need to be grounded in the present world, but I want to avoid idealistic portrayals of reality while still showing hope and beauty from ashes.

The idea of beauty from ashes comes from Isaiah 61 and has inspired much of my work. It’s about showing beauty amidst destruction and within brokenness. For instance, my painting Agnus Dei has the ruins of a cathedral reflecting the persecution of the church but also its moral compromises. The animals in the painting are calling us to moral faithfulness to God, the Creator.

In The Greening of the White Cube, where Sophia walks into an abandoned art gallery, there’s a deer that has already entered the space before her. The animals serve as signposts. One passage that inspired the Vanitas and Viriditas series is from the Book of Job, chapter twelve, which says… “But ask the animals, and they will teach you. Who among them does not know that the Lord holds the breath of every creature?” Animals have this abiding divine awareness, and that’s where I see hope, which points toward the new Eden.

Similarly, in The Peaceable Kingdom, a painting in progress at the exhibition, I’m interested in the liminal space between the fallen world and the world of new creation, instead of jumping straight to paradise or heaven. It’s very hard to paint that in a believable way. If I’m being honest, what I’m doing is portraying something I can more realistically capture with my knowledge of the broken world we’re living in.

Traces: I appreciate you mentioning the Canadian influences of Charles Taylor and Margaret Atwood. Your painting Creation Cathedral pulls directly from Emily Carr’s The Indian Church. As a contemporary Canadian painter, where does your work fit in the larger traditions of Canadian art and culture?

JT: I get interviewed by American art magazines, and they’ve never heard of the Group of Seven or Emily Carr, with some exceptions. But I would say one thing that gets overlooked in that discussion is the spiritual impetus behind a lot of Canadian works. For the Mystical Landscapes at the Art Gallery of Ontario, Dr. Rebecca Smick (Professor of Philosophy and Art at the Institute for Christian Studies) wrote in the exhibition catalogue about how the survey highlighted the presence of God within creation in modern landscape painting. Granted, the curators also referenced the influence of Theosophy, Buddhism, and other spiritual traditions, but they rightfully questioned the conventional secularist narrative.

I was thinking through how a lot of Canadian art includes Indigenous voices, as they similarly refer to animals as our brothers and sisters within creation, which I thought was quite meaningful. Emily Carr writes about seeing God in His woods, in the Tabernacle of the woods.

There’s this interesting tradition in Canadian art. Although I don’t only paint the Canadian landscape, there is a sensibility in Canadian art—an affection for the natural environment and our beautiful country. This goes back to indigenous artists like Norval Morrisseau, the Anishinaabe artist, and Kenojuak Ashevak, the Inuit artist. When post-Impressionist painters came from Europe and were exposed to Canada’s colourful landscapes—like Lawren Harris’s mountains, which have this transcendent and uplifting quality—they were inspired by the beauty. But on the other hand, we have painters like William Kurelek, who included themes of depression and existentialism. He was a man of faith, but there are a lot of winter scenes in his works where you feel the sense of a barren landscape. So, there is this interplay of beauty in the landscape but also isolation and despair.

It is necessary for us to highlight some of these overlooked spiritual narratives and tensions, as well as the strong environmental art tradition, both of which I see myself benefitting from and hopefully being a part of. So, I do feel like I fit within that sensibility of relating to and wanting to steward our landscapes, as an individual, a Christian, and an artist.

Maya Venters is a writer from the Canadian East Coast. Her chapbook Life Cycle of a Mayfly (Vallum Chapbook Series) won the 2023 Vallum Chapbook Prize. She is an MFA candidate at the University of St. Thomas (TX) where she received a Scanlan Fellowship. Maya has published in Rattle, The Literary Review of Canada, Modern Age, and Ekstasis, among others. She can be found at mayaventers.ca.